As a young Jesuit, Bergoglio had heard one of Angelelli’s social Gospel sermons wherein he gave the advice that evangelization means “one ear to listen to the word of God and one to listen to the people.” That God speaks to the Church through “the people,” meaning the poor and the oppressed but not the contemptible wealthy elites Francis never ceases denouncing, is a prime tenet of Liberation Theology and its justification for revolutionary movements.

No proof of miracles was necessary, nor was any forthcoming. It sufficed that Bergoglio had deemed Angelelli a martyr on account of his “commitment to social justice and to promoting the dignity of the human person.” There was no suggestion that Angelelli had been killed on account of hatred of some article of the Catholic faith. Indeed, even assuming he was murdered—an assumption unsupported by any real evidence, as discussed below—for all we know his alleged killer or killers, who probably would have been Catholic themselves, might have considered that it was Angelelli who hated the Faith. After all, faithful in his own diocese had already dubbed him “Satanelli.”

This preposterous beatification outdoes even that of Oscar Romero as a mockery of the beatification process. Over the past six years, Bergoglio has definitively demonstrated the fallibility of beatifications while undermining even confidence in the general opinion of theologians that canonizations are infallible, given his patently ideological determination to canonize every Pope involved with the Second Vatican Council, including the hapless and immensely destructive Paul VI, as to whom there was no preexisting cult nor any unambiguous miracle worked by his purported intercession.

Before discussing the imposture of this beatification, some historical context for Angelelli’s ill-starred ecclesiastical career is in order.

Rise of a Clerical Rabble Rouser

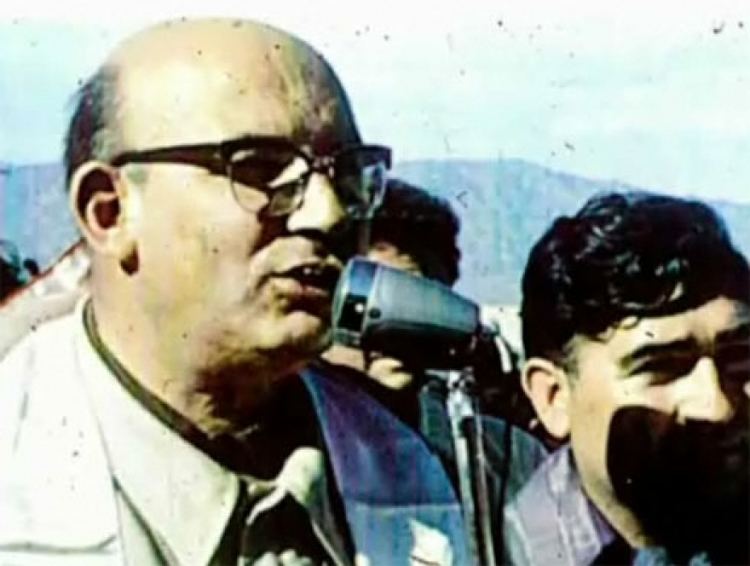

Archbishop Angelelli

Archbishop Angelelli

From 1930 to 1976 Argentina, which in the previous century had been “liberated” from Spanish rule by the usual cabal of Masonic revolutionaries, had 19 different presidents following the military coup that overthrew Hipolito Yrigoyen. From 1946 until 1955, Juan Perón’s collectivist dictatorship, home to ex-Nazis but also quite friendly to Jews, held sway. Resistance to the Peronist regime was met with violent repression by its allied para-military organization, the Nationalist Liberating Alliance (ALN). (Lewis 2002, p. 14 ff)

To the relative right of Perón were Argentina’s “conservative” elites, whose standard post-colonial political liberalism included acceptance in principle of civil marriage, the separation of Church and State, public education in secular schools and laissez faire capitalism. The basic dynamic of Argentinian politics was a conflict between leftwing and rightwing Peronism, a conflict Perón’s entire career of expedient right-left shifting—like that of Bergoglio!—exhibited. (Lewis 2002, pp. 14-16)

By 1955 Perón’s regime had drifted decisively leftward as he “threatened the separation of church and state, ended religious instruction in state schools and planned to legalize divorce and prostitution.” (Cavendish, 2005) The Catholic Church’s growing opposition to Perón’s expanding dictatorship had managed to unite “employers, middle-class professionals. Radicals, conservatives, socialists, devout Catholics and restive military officers.” (Lewis 2002, p. 19)

In the summer of 1955, after Perón deported two Catholic priests to Italy and ALN militias burned Catholic churches in downtown Buenos Aires, Pius XII issued a decree excommunicating the officials responsible and by implication Perón himself, although he was not named. A military coup headed by General Eduardo Lonardi ended the Perón regime in September of that year. (Cavendish, 2005) But Lonardi was in turn overthrown by yet another coup, headed by his own Vice President, General Pedro Aramburu. Aramburu’s program of purging the country of extreme leftwing elements of Peronism failed when, with the support of Perón who was now in exile, the leftist radical Arturo Frondizi was elected President in 1957. Then the Peronist Party, energized by the prospect of Perón’s return to Argentina, won the midterm elections of 1962. The threat of another leftward drift provoked yet another military coup. This was followed by the tenuous civilian governments of Jose Maria Guido and Arturo Illia and then still another coup in 1965 and the installation of General Juan Carolos Ongania as President, with Perón all the while plotting his return from exile. (Lewis 2002, pp. 14-25)

By then the slogan “Perón Will Return” was appearing “all over the walls of Argentina’s cities” and Perón advised his loyal subaltern, John William Cooke, to use all means, including violence, to secure his return to power:

If it’s necessary to use the Devil, then we’ll use the Devil as we must. The Devil is always ready for such work.” (Lewis, 22-23).

The Resistance movement gained strength as the emergence of leftwing Peronist guerilla groups engaging in bombings and assassinations paved the way for the Dirty War later waged against them by the junta. In 1973, these groups “would merge with the Montoneros,” then a “small band of urban terrorists” that got the ball rolling by kidnapping and then assassinating Aramburu in retaliation for the anti-Peronist measures he had adopted while in power. The Montoneros exhibited what Mitchell Abidor has called “an almost Christ-like veneration of the Perons”—i.e., Juan and his late wife Eva (“Evita”) Peron, the quasi-sainted social justice hero of the Argentinian working class. (Abidor, p. 1)

Perón (right)

Perón (right)

After his triumphant return to Argentina following the elections of 1973, Perón distanced himself from the Montoneros even though their terrorist violence had been “a key element in his strategy for return to power.” (Ibid.) After a Montonero hit squad assassinated Jose Rucci, head of one of Argentina’s most powerful labor unions, Perón repudiated them decisively. In a speech on May 1, 1974, he denounced them to their faces as “stupid” leftists as they skulked away from the crowd in the plaza. (Ibid.)

By the time Perón died of a heart attack in 1974, the Montoneros had become an underground terrorist organization with above-ground “peaceful” associates. Along with communists and other leftists, they waged non-stop guerrilla warfare against the military government that succeeded Perón and was waging the Dirty War against leftist insurgents of all stripes from 1974-1983. By 1979, however, the Montoneros had “ceased to exist as an active force.” (Abidor, p. 2).

Enrique Angelelli It is in this historical context that “Blessed” Enrique Angelelli was made Bishop of the Diocese of La Rioja by Paul VI in 1968—one of Paul’s innumerable blunders. A rabble-rouser, labor organizer and supporter of socialist and communist currents, including the Montoneros, Bishop Angelelli also defended against accusations of heterodoxy the Castroite “Movement of the Priests of the Third World,” which in 1969 issued a declaration in support of socialist revolutionary movements, prompting the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires to issue a prohibition on such political declarations by priests. With Angelelli, observes one commentary, “the discipline, the integral custody of the Faith, was converted into ‘dialogue’ with those who publicly promoted heresy and violence from within the hierarchy of the Church.”

It is in this historical context that “Blessed” Enrique Angelelli was made Bishop of the Diocese of La Rioja by Paul VI in 1968—one of Paul’s innumerable blunders. A rabble-rouser, labor organizer and supporter of socialist and communist currents, including the Montoneros, Bishop Angelelli also defended against accusations of heterodoxy the Castroite “Movement of the Priests of the Third World,” which in 1969 issued a declaration in support of socialist revolutionary movements, prompting the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires to issue a prohibition on such political declarations by priests. With Angelelli, observes one commentary, “the discipline, the integral custody of the Faith, was converted into ‘dialogue’ with those who publicly promoted heresy and violence from within the hierarchy of the Church.”

Angelelli had, in short, aligned himself with Argentinian socialists and communists in the midst of a bloody civil war. As Rorate Caeli observes:

There were many radical bishops in the wild years following the Second Vatican Council. But Enrique Angelelli, bishop of La Rioja, Argentina, was probably the most radical. He was a Communist in all but name and stridently supported the terrorist organization “Montoneros”, the leftist terrorist branch of the Peronist movement. It can be undoubtedly said that the horrid military dictatorship that governed Argentina from 1976 until the Falklands War was brought about as a brutal overreaction to the terrorist attacks coordinated by Montoneros in favor of a Socialist-Peronist revolution. Angelelli was so leftist, so radically leftist and so political, that the shocked practicing faithful of his own diocese used to call him in life “Satanelli.”

In 1970, notes the aforementioned commentary on Angelelli’s ecclesiastical career:

Angelelli's friends and political discussion companions at the Priestly Home of Córdoba, Ignacio Vélez and Emilo Maza, participated in the attack on a military unit in La Calera. The event was also attended by the priest Erio Vaudagna, one of Angelelli’s former collaborators who, at La Rioja, compared them with the Apostles: “They were also told that they were subversives.” …. The subversive, revolutionary and terrorist armed struggle was publicly encouraged and reified by Bishop Angelelli.

Angelelli’s radical leftist sympathies were known to all, not just the junta and its death squads. Indeed, as Rorate Caeli notes, the nickname “Satanelli” emerged from the lips of the very faithful over whom Paul VI had placed Angelelli as bishop. To quote once again the extended commentary:

On November 9, 1972, the chaplain of a Catholic school, before all the parents assembled, rebuked him for his bad doctrine and tried to expel him from the celebration commemorating the school’s founding. Priests and faithful organized to resist the Castroism of the Bishop of the ‘Renewing Crusade of Christianity.’ And this shows clearly that the opposition to Angelelli was not born in the [military] barracks as his panegyrists pretend to believe, but rather originated with the clergy, parishioners and the whole people, who saw Angelelli destroying the faith they had inherited from their parents.

A Beatifical Fraud

Returning to the question of Angelelli’s “beatification,” it is not only ludicrous but fraudulent to attribute his death in 1976 to odium fidei. First of all, Angelelli died in a car accident on August 4 of that year. The autopsy report confirmed injuries consistent with the accident and found no suspicious circumstances.

Immediately, however, Angelelli’s partisans began to construct the fable that a mysterious vehicle had pushed the bishop’s car off the road and that the accident was a homicide perpetrated by mysterious agents of the junta, who were never identified. Finally, in 1986, based on nothing but rumors, a criminal case was opened in the criminal court for Rioja in which Judge Aldo Morales, without competent evidence, ruled that Angelelli’s death had been a homicide caused by unknown government assassins who had run his car off the road. The driver of the car, Angelelli’s diocesan vicar Father Arturo Pinto, who had claimed lack of memory after the accident on account of trauma, now conveniently changed his story , claiming his car had been followed by another car that struck his and caused it to roll over.

Morales ignored a sworn declaration submitted by Bishop Bernard Witte, Angelelli’s wholly orthodox successor, in which an eyewitness who was working on the tower of a high tension line at the time recounted that the Fiat 125 in which Angelelli was riding veered onto the shoulder and that Pinto, overcorrecting, caused the car to flip, expelling Angelelli, who died on impact. The witness denied seeing any other vehicle at the scene.

In 1989 the federal prosecutor, Luis Roberto Rueda, derogating from Morales’ decision, informed the Federal Appellate Court of Cordoba that “the related judicial declaration is not correct insofar as it affirms that the death of the Bishop was due to a homicide, because the objective proof on which the reasoning is based is weak.” (Ares, 2012) In 1990 that Court, agreeing with the prosecutor, declared the proof insufficient and ordered the case provisionally dismissed, noting in its opinion that of the two “witnesses” Angelelli’s partisans had produced, one had provided conflicting versions of his story while the other, under oath, denied that he had ever been at the scene on the day of the accident. (Ibid.)

It was not until 2014, under the leftwing government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, that a different court, the Federal Verbal Tribunal of Criminal Causes in La Rioja, “reached an opposite conclusion,” blaming the accident—again without real evidence—on two military officers of the former junta, now both in their eighties. One of the two was already serving a life sentence under Kirchner’s program of convicting the government side of the Dirty War of “crimes against humanity” (continuing the program of her husband, former President Nestor Kirchner) while ignoring the assassinations and deadly bombings committed by leftwing terrorists.

The respected Argentine journal La Nacion, which is actually favorably inclined toward Bergoglio, has published a scathing critique of the beatification (translation by Rorate Caeli) which observes that the two officers were deemed guilty “as ‘indirect’ perpetrators, a legal construction that has been abused in this kind of trials. In this case, it allowed the conviction of hierarchical superiors of a crime that was never proved, and in which there are no ‘direct’ perpetrators at all. The verdict considered certain that the rollover of the car in which Angelelli travelled had its origin in an intentional maneuver by another vehicle that was following orders given by military chiefs.”

Which military chiefs in particular did not seem to matter, and one already imprisoned for life would do very nicely. Nor did the Court seem at all concerned about identifying the actual perpetrators of the alleged vehicular homicide, evidently considered a trivial detail on the way to the desired outcome. Both officers have adamantly maintained their innocence.

Even Crux magazine, full of praise for the “beatification,” grudgingly reports good reason to think something very fishy was going on with the new finding of guilt: “Another element of Angelelli’s sainthood case that has raised doubts is the fact that the documentation didn’t include the full report of the car accident in which he was killed. Though two people have been condemned for it, there’s a witness who says he heard the accident and there was no second car involved, meaning no one to throw the bishop’s car off the road.”

But what need was there for witnesses or the identity of the actual perpetrators? Bergoglio and his collaborators wanted this beatification, so the required “murder” was supplied by pinning notional vicarious guilt on two aged military officers who will soon be dead themselves.

But what need was there for witnesses or the identity of the actual perpetrators? Bergoglio and his collaborators wanted this beatification, so the required “murder” was supplied by pinning notional vicarious guilt on two aged military officers who will soon be dead themselves.

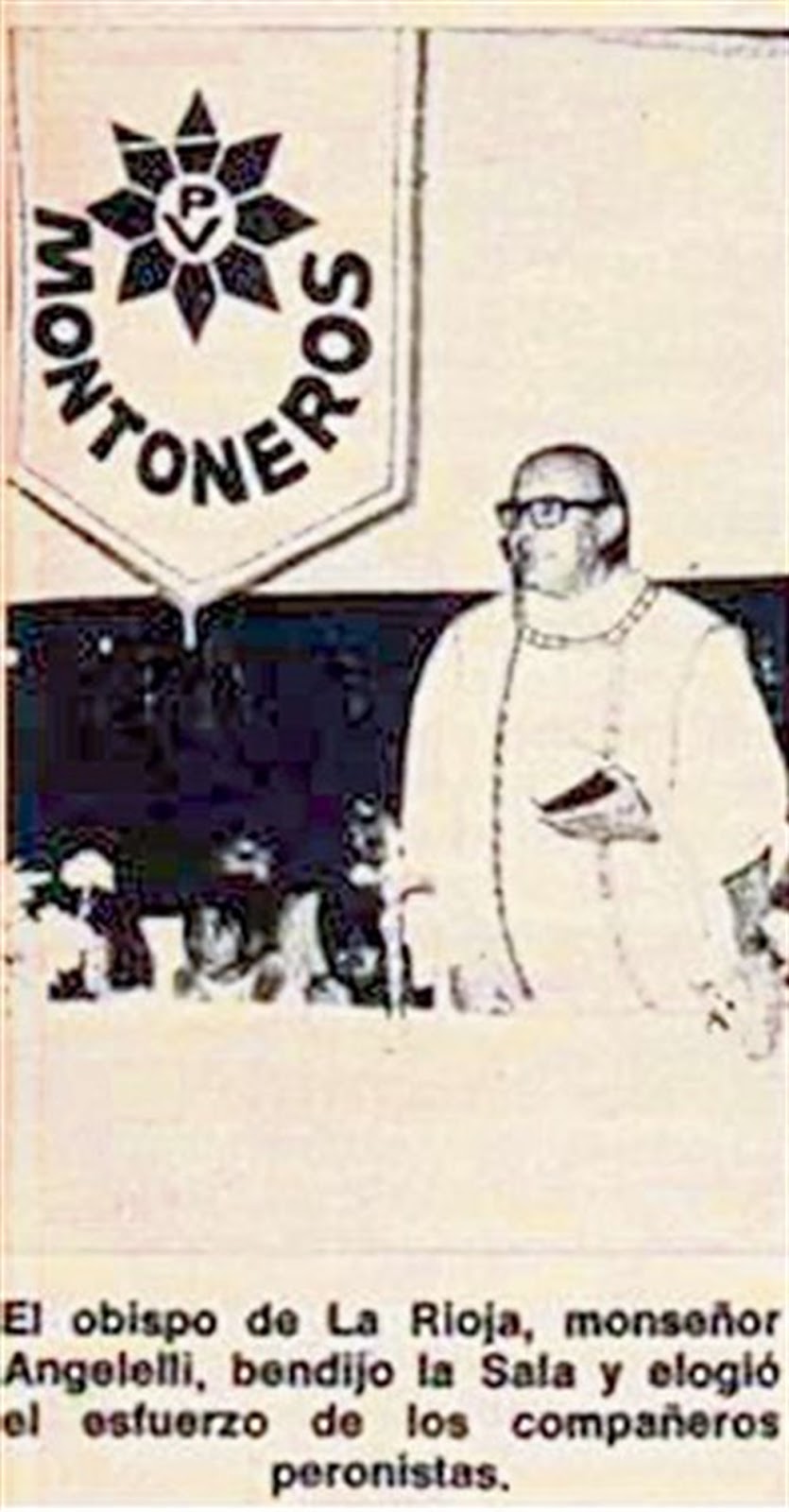

At any rate, as La Nacion further observed: “Even if, hypothetically, it had been a murder, Angelelli would not be a martyr for defending the faith. The La Rioja bishop had an active and proved link with the terrorist organization Montoneros. In the photo that illustrates this text [reproduced above], he is seen celebrating mass with the banner of this organization at his back, while in his homilies he spoke in favor of uprising and proposed arming young people.” (Attempts to explain away the presence of the banner as a sudden improvisation at that particular Mass, of which Angelelli was not aware beforehand, do not alter the reality that, like everyone else in Argentina at the time, he had to know of the terrorist elements in the movement he encouraged and supported.)

Angelelli’s rabble-rousing sermons did not merely protest true injustices in Argentinian society, which certainly existed, but openly incited the revolt of the Marxian proletariat in the midst of ongoing terrorist violence aimed at the overthrow of the junta. For example, one website containing a glowing tribute to the “martyr” quotes these bromides of liberation theology from one of Angelelli’s sermons, stoking the resentment of the poor against the rich and invoking the theme of class warfare to topple the “systems” of oppression:

We are living an historic hour where the changes are profound in the mentality of men and in the structuring of human society. There are systems ... that cause many sufferings, injustices and fratricidal struggles. Many men suffer and the distance that separates the progress of a few and the stagnation and even the retreat of many increase. The present situation has to bravely face, fight and overcome the injustices that it brings….

The people are the ones who do not oppress but fight against oppression… The anti-people are the force that responds to outside interests. It is personified in a minority that wants to preserve its privileges. It is the one that prevents the growth of the people and struggles to plunge it into oppression and slavery. It is the one that slows down our history….

Here we see the false Gospel of liberation theology according to which the poor fight against their oppressors to establish social equality.

In short, if Angelelli was murdered it was on account of his politics, not his religion. As Crux reports in the linked article, the defenders of this sham practically admit as much: “Father Luis Escalante, another Argentine priest, told Crux that Angelelli wasn’t killed in odium fidei, meaning in hatred of the faith, which is the most common cause for a person to be declared a martyr. ‘The bishop wasn’t murdered for his faith, but his faith-based defense of social justice.’”

But the requirement of odium fidei is not merely “the most common cause” for beatification, it is the only cause as Tradition attests: “[A] martyr, or witness of Christ, is a person who, though he has never seen nor heard the Divine Founder of the Church, is yet so firmly convinced of the truths of the Christian religion, that he gladly suffers death rather than deny it…. Yet, it was only by degrees, in the course of the first age of the Church, that the term martyr came to be exclusively applied to those who had died for the faith.” (Hasset, 1910)

As Cardinal Becciu himself admitted, Angelelli’s “faith-based” actions did not actually involve the Faith: “He undertook the defense of these poor people by creating unions and cooperatives, and his action, like that of the other three martyrs who will be beatified, did not please the strong powers of the time so they were eliminated.”

In other words, Bergoglio has invented a new ground for beatification: working for “social justice” in opposition to civil authorities. But if martyrdom means being murdered on account of such activities as labor organizing and forming cooperatives, which is no part of the divine commission or the divinely appointed duties of a descendant of the Apostles, then martyrdom no longer has anything to do with Catholicism as such. Indeed, any Marxist social justice warrior could receive what John Vennari so aptly dubbed a “Halo Award” should he die at the hands of a government agent.

Angelelli and a symbol of violence Yet Angelelli’s meddling in a civil war between an admittedly brutal military government and its just-as-brutal leftist guerilla opposition was precisely the opposite of what is expected of a saint: that is, the imitation of Christ, who refused to be involved with or endorse in any way revolutionary insurrection even against the Roman dictator whose procurator would sentence Him unjustly to death.

Yet Angelelli’s meddling in a civil war between an admittedly brutal military government and its just-as-brutal leftist guerilla opposition was precisely the opposite of what is expected of a saint: that is, the imitation of Christ, who refused to be involved with or endorse in any way revolutionary insurrection even against the Roman dictator whose procurator would sentence Him unjustly to death.

As the aforementioned commentator mordantly but fairly enough observes, Angelelli was “a bishop who instead of being a follower of the Apostles of Pentecost, followed Judas.” For it was Judas who was scandalized by the Passion and wanted Our Lord to lead a rebellion against Caesar, and it was he who rebuked Mary Magdalene for lavishly anointing the feet of Our Lord in anticipation of His Passion, declaring: “Why was not this ointment sold for three hundred pence, and given to the poor?” (John 12:4-6) As Saint John writes: “Now he said this, not because he cared for the poor; but because he was a thief, and having the purse, carried the things that were put therein.” Likewise thieves are all the socialist tyrants enabled by liberation theology and coddled today by Francis, robber barons who mercilessly exploit the impoverished masses of Latin America while they live in luxury, being among the very elites Francis loves to condemn, but only when they are capitalists—or rather certain capitalists, as Bergoglio the Peronist-style demagogue is quite comfortable with the plutocrats who serve his globalist agenda. Then there is the Bergoglian sellout of Chinese “underground” Catholics to the butchers of Beijing, who lord it over the teeming masses on whom they impose forced abortions while they relentlessly pursue the “sinicization” of the Church in China, which they declare “independent” from Rome.

“Blessed” Enrique Angelelli is hardly what the Church envisions as a beatus. But he is certainly Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s idea of a saint. Here, as elsewhere, Bergoglio has imposed his own ideas upon the Church, heedless of anything to the contrary in her traditional teaching and practice. In a papacy already bereft of all credibility, Pope Bergoglio has managed to find a new low. All the better, one supposes, for the case in support of a successor’s negation of his entire pontificate.

Sources:

Mitchell Abidor, “The Montoneros,” www.marxists.org/history/ argentina/montoneros/ introduction.htm; accessed April 27, 2019.

José Fernando Ares, “La Mentira del Asesinato de Angelelli” (The Lie of the Assassination of Angelelli”), April 1, 2012; accessed at www.quenotelacuenten.org/2018/06/10/ angelelli-el-crimen-que-fue-un-accidente/

Richard Cavendish, “Juan Perón Overthrown,” History Today Volume 55 Issue 9 September 2005; accessed at https://www.historytoday.com/archive/juan-per%C3%B3n-overthrown.

Hassett, M. (1910). Martyr. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. (New York: Robert Appleton Company). Retrieved April 28, 2019 from New Advent http://www.newadvent.org/ cathen/09736b.htm

Paul H. Lewis, Guerrillas and Generals: The “Dirty War” in Argentina (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishing, 2002).