Picture, if you will, this wonderful gentleman of, say, eighty years, sitting next to the fire in his great big favorite chair, puffing on his old pipe. Smoke gently lifts from the black, charred bowl, and it hangs in the warm glow of his lamp in striking patterns and swirls. His steely gray hair lies back, still in full complement across his brow, and his eyes begin to sparkle as he takes one last puff, rubs his chin bemusedly, surveys his small audience of loved ones, and begins to tell the story of a Christmas which took place more than a half-century ago.

Quietly, his story begins…

It was in North Africa, near a place called Libya. I guess the year must have been 1943. What an extraordinary time it was to be alive. There I was, a young writer, full of dreams and aspirations one minute, and the next thing I knew I was being loaded onto a boat with two thousand other GIs and sent off to fight another war in Europe. I was with the 323rd Air Service Command, and I remember thinking how strange it was that I was off to fight Germans, some of whom no doubt would be relatives of mine who hadn’t gotten out before the brutal Third Reich had closed Germany’s borders.

I had aunts and uncles and cousins and even grandparents trapped in Germany when Hitler came to power. Hitler, what a madman! That paper-hanger from Munich even managed to butcher the German language. How we hated the barbaric manner in which he shouted the German language.

I guess that moment, as the New York harbor fell away behind us in the wake of our troop ship was one of the most peculiar I’d ever experienced—it barely felt real, in fact.

Reality set in soon enough. My career as an Army sergeant of the 323rd took me all across Africa, Egypt, the Middle East, Italy, and finally even Rome itself. Ah, now that was another grand moment. When we marched into Rome in 1944 I never heard so many church bells ringing in my life. The air was bright and fresh, and it positively crackled with excitement; the Nazis had fled, Mussolini was finished, and there, high over the piazza, stood a white figure blessing the Allies as we marched into the Eternal City—it was Pope Pius XII.

How did I feel at that moment? I wept for joy! That image of Papa Pacelli standing over us and giving his blessing to a sea of GIs is something I’ll never forget. The Church seemed to strong then. We didn’t know it, but Pius XII was the last of the Old Guard to sit in Peter’s chair. A new breed was waiting in the wings and revolution was in the air.

But, I lose myself. We were, as I said, at a place near Libya, in North Africa. General Rommel—the Desert Fox, as they used to call him—had led the Allies on a merry chase across Africa, and somehow, even as Christmas approached, the 323rd ended up at Libya.

When I think back now I can’t really recall any moments when the sand wasn’t blowing like snowflakes in blizzard back home. It was becoming a long war for us. We were tired of sand; we were sick of Wings and Cravens (cheap cigarettes) and we were homesick. There wasn’t a guy in our outfit who didn’t want to be anywhere but in Libya that December. But, just the same, Christmas was coming, and we weren’t going anyplace else.

I guess war can bring out the best and the worst in a man. For the 323rd war was bringing out the worst. Even the prospect of Christmas could do little to lift the spirits; in fact, it seemed to make things even worse. You have to remember that we had been overseas for better than two years. The war raged on, the propaganda rolled in, the war machine rattled along, and all anybody wanted to do was to go home, see his family, kiss his girl, hug his baby, and wish the war on the moon. But instead of all that, we had only two things to think about— Nazis and sand. Which was worse?

For me, Christmas was the hardest time to be at war. I would sit at night in the tent and listen to the howling wind and biting sands beat against the canvas. Sometimes the faint and scratchy strains of White Christmas would bring a bit of cheer, though I was never terribly fond of “der Bingle”—Bing Crosby.

Still, as the familiar tune would come over the camp’s public address system, my thoughts would drift over Europe and the Atlantic, and I would think of my dad and mother, my sisters and brothers, all sitting around a wartime Christmas tree, wondering when the war would end, wondering if I was to come home, wondering if Nazis or Japs would land on America’s shores.

Inevitably that musing would be interrupted by an eerie buzz, high over head. It would grow louder, and then the air raid sirens would make it official: enemy bombers! Any thoughts of home vanished in the blackout that would follow. A weird shower of light was falling from the heavens—Nazi flares on shoots, descending to light the desert floor and to illuminate potential targets—us. Sometimes the bombs were on target; sometimes not. In my case… well, I guess I had a good guardian angel.

Anyway, by the time Christmas Eve morning dawned that year I was in a real mutz. My tent mates looked surly, my C.O. was a bear, and even the cooks in the mess hadn’t much Christmas cheer to spare. By late afternoon, I was downright depressed. What a Christmas, I thought. Merry Christmas indeed!

The next issue of The Remnant is the 2014 Christmas issue, with a soldier's true story of another Christmas Eve Mass, only this time in Viet Nam. Don't miss it! Subscribe today:

But then a wonderful thing happened. A few of us had been wondering if we would be granted leave in honor of the day as we had requested, but up until that point there hadn’t been any word. A runner came in just then with a note from the C.O.’s office, which read simply, “Leave granted. Twenty-four hours.”

Well, it wasn’t much, especially in the middle of the desert, but it was something. Three of my tent mates were Catholic, and a Brit from the Red Cross had spoken of a Mass that was scheduled to take place on Christmas Eve at midnight. He was a bit vague on the directions but it was supposed to be held a few miles across the sand, east of our encampment at an old ruin of some kind.

We had been given leave and that was all—no truck, no jeep, not even a lorry. And by the time we were ready to go, the sun had already set.

I remember feeling invigorated that night as we set out. The night sky was clear, and visible to the four of us was a starry canopy such as I have rarely seen. The light given by a million desert stars shown across the white endless sand as we walked along, gradually realizing that for the first time in months our spirits had begun to lift.

Some time later, however, one of us said something the rest of us were afraid to admit—“We’re lost.” And so we were. It wasn’t that we could not find our way back but rather that we saw nothing on the darkened horizon to lead us to believe that somewhere ahead a Midnight Mass was to be offered. Time passed, until we reached the point where the only sensible thing was to head back to camp.

There we were, four GIs in the middle of a desert—lost and alone on Christmas Eve. It was my old tent mate Bob who first noticed the change come over us as we walked. It was like the moon had risen in the night sky but there was no moon that night. As we walked along we suddenly found ourselves tromping on the shadows of the guy walking in front of us, cast by a strange light high in the heavens and off to east. It was a star—the most brilliant and dazzling star any of us had ever seen. We all stopped in our tracks and looked up. No one said a word until all at once Bob chuckled exactly what each of us had already been thinking, “Sort of the like the star of Bethlehem, eh boys?”

Now, I will not claim that that the star actually moved out in front of us. But, then again, it did hang so low on the horizon, and it was so unusually bright that we all continued walking toward it, not really knowing what to make of it.

We continued to walk. Soon we realized that we were not alone. Dark shapes of men, whom we first mistook for Bedouins, suddenly appeared in the night and moved toward a place that was located directly ahead of us now, beneath the brilliant white star. They were not Bedouins, nor were they ghosts; they were other GIs, Brits, Aussies, Canadians, Frenchies, and Scotties—Catholic soldiers from other encampments, coming like a night caravan to find the place where the Christmas Mass was to be offered.

Our pilgrimage followed a gradual incline over a low line of dunes. On the other side, we saw it—a massive gathering of thousands of soldiers, many of them the most weather-beaten fighting men you’ve ever seen; all come to find the place where the Mass was to be said, at midnight, on Christmas Eve, in the middle of a world war.

A similar wartime Mass from the day and age when all Catholic men were traditionalists, who heard Mass in Latin and who knelt to receive Our Lord on the tongue. Excitedly, the four of us made our way through towards our brothers-in-arms. We were walking through a veritable sea of Catholic men, waiting on the sand for Mass to begin. There wasn’t much of the usual fighting and swearing and drinking going on. The spirit of Christmas seemed to have transformed the boys into the sons, the brothers, the husbands, and the fathers they had all once been not so very long ago. Now they were only Catholic boys like me, desperate for some spiritual nourishment.

Excitedly, the four of us made our way through towards our brothers-in-arms. We were walking through a veritable sea of Catholic men, waiting on the sand for Mass to begin. There wasn’t much of the usual fighting and swearing and drinking going on. The spirit of Christmas seemed to have transformed the boys into the sons, the brothers, the husbands, and the fathers they had all once been not so very long ago. Now they were only Catholic boys like me, desperate for some spiritual nourishment.

“Hey, Chappy, I need to confess,” someone said. “Me, too!”

The Catholic priest smiled, “Okay, boys, let’s form a line.”

He was dressed in an Eisenhower jacket with a tiny purple stole around his neck. A moment later, a GI was kneeling at his side. Instinctively, I fell in line a few paces behind and waited my turn.

The next thing I can recall is kneeling in a expansive gathering of men. Some fifty paces ahead, I can see a truck with a lowered tailgate, a vested priest standing next to it. Surrounded by a sea of dark faces, dusty helmets, thousands of Springfield rifles, and glistening eyes, I see myself as a solider again, looking on as the sacred moment arrives on that holy night. Through a thousand shadows of lowered heads and hulking shoulders. I hear a bell and I see a brilliantly white Host raised high over the “tailgate altar” for thousands of battle-weary troops to adore.

For just an instant, I have a clear view of the Host through the wall of soldiers, and, in that moment the light of the star seems to envelope the Host. A bell rings again in the desert stillness and then the Host is lowered from my view.

I knelt in the sand, facing east, towards the City of David. Across the desert and over the hills of Galilee was the little town of Bethlehem—the place where the Sacred Victim had been born into this world, in a stable so many years ago. And yet, there was I, beneath another shining star in the middle of another war, paying homage to that same tiny Child. It was a defining moment in my life as a Roman Catholic. I will never forget it.

The gentleman pauses momentarily, in deep reflection. He takes another puff on his pipe and continues…

Then the scene before my eyes was blurred by my tears, I don’t know if they were of joy or sadness or both; but I had crossed back over the Atlantic; the war was over, and I was home—for just a few moments, I was home. Time stood still. Then I heard the murmur of song begin to move through the great gathering of soldiers. It was a familiar song to me; it was “Silent Night.” You have never heard “Silent Night” until you have heard it six thousand miles from home in the starlit desert of North Africa and sung by thousands of homesick GIs, after Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve.

I filled my lungs and I sang with all my strength that night: “All is calm, all is bright. Round yon virgin mother and Child, Holy Infant so tender and mild. Sleep in heavenly peace. Schlaf in Himlisher ruh.”

For that is what it was –a silent night! A night in which the holy blessing and grace of Christmas filled a war-torn desert with heavenly peace. I surely was not the only GI to brush away a tear into the desert sand that night.

The war finally did come to a merciful end, and I came back home. But, you know, every now and then, I think back to that Midnight Mass in 1943 and I think, “That was the closest to Heaven I’ve ever been.” That silent night is what Christmas is all about, and I know I’ll never forget it.

And then, with a gentle smile and another puff on the old pipe, his story comes to an end.

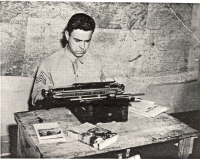

Walter Matt, Libya, World War II (1943)

Walter Matt, Libya, World War II (1943)

Editor’s Note: The following was first published in The Remnant many years ago. We’re publishing it again now in memory of the founding editor of The Remnant, Walter L. Matt, who went to his eternal reward in 2002. The article was written by the present writer when he was much younger, and it is essentially a retelling of the true story my father used to tell his nine children about an experience one Christmas Eve during World War II. Please remember him in your prayers. MJM

Introduction

The story I am about to tell is most assuredly a true one. It is a story told to me by a war veteran of the Second World War, and he assures me that this story is not an invention. This old soldier is very much in earnest, and, although it is my pen that puts these words before you now, it is his voice that spoke the words to me. And his words are true. I write the story for you exactly the way I heard him tell it—first when I was a boy, and once again, not long before he passed away.

Michael J. Matt | Editor

Michael J. Matt has been an editor of The Remnant since 1990. Since 1994, he has been the newspaper's editor. A graduate of Christendom College, Michael Matt has written hundreds of articles on the state of the Church and the modern world. He is the host of The Remnant Underground and Remnant TV's The Remnant Forum. He's been U.S. Coordinator for Notre Dame de Chrétienté in Paris--the organization responsible for the Pentecost Pilgrimage to Chartres, France--since 2000. Mr. Matt has led the U.S. contingent on the Pilgrimage to Chartres for the last 24 years. He is a lecturer for the Roman Forum's Summer Symposium in Gardone Riviera, Italy. He is the author of Christian Fables, Legends of Christmas and Gods of Wasteland (Fifty Years of Rock ‘n’ Roll) and regularly delivers addresses and conferences to Catholic groups about the Mass, home-schooling, and the culture question. Together with his wife, Carol Lynn and their seven children, Mr. Matt currently resides in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Latest from Michael J. Matt | Editor

- NEOCONNED: Jeffrey Sachs, Tucker Carlson, and Michael Matt on Israel’s War

- THE RESURRECTION of NOTRE-DAME: A Triumph of the Immaculate Heart

- CHRISTIANS in the CROSSHAIRS: Bombs over Bethlehem, Assad flees Syria

- GENOCIDE: Jews, Traditional Catholics Protest Israel's War

- First Mass at Notre Dame de Paris: a few quick reactions