Unfortunately, the following day, March 2, the infamous and ruthless General Eulogio Ortiz Reyes (1889-1947) also arrived at his new assignment, also in Valparaiso. Tyrannical head of Military Operations, an anti-Catholic persecutory arm of authority, he was a soldier of the worst sort, a Socialist veteran of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) and a Callista: a follower not of Christ, but of the Christophobic president of Mexico, Plutarco Elias Calles (1877-1945).

Almost immediately after Ortiz’s arrival, the general – known unaffectionately as “Eulogio the Cruel” – ordered the new pastor, Correa, and his vicar, Father Jose Adolfo Arroyo (1893-1938), to report to his office.

“What is your work here?” Ortiz demanded of Correa.

“Work of peace,” the new pastor answered.

“This is work of peace?!” Ortiz fumed, holding out a piece of paper.

“The priest does not know about the manifesto,” interrupted Arroyo, “because he just arrived.”

“Yeah, sure, he doesn’t know about it,” Ortiz said sarcastically and yelled, “He just arrived and is raising hell!”

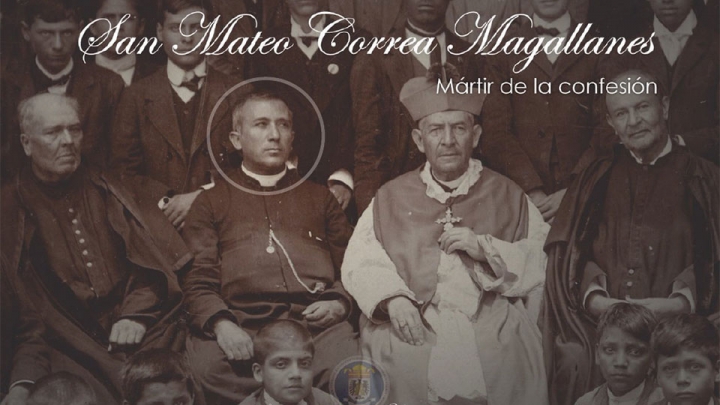

Even though facing arrest and possible execution for each religious act of his Catholic vocation, Father Mateo Correa Magallanes persevered and continued to tend to his persecuted flock.

The manifesto focused on gathering signatures for a national referendum – spearheaded by the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty – that would be dispatched to the Congress of the Union, requesting the repeal of anti-Catholic laws contained in the 1917 Political Constitution of the United Mexican States.

Ortiz bombarded Correa with questions: Why he was in Valparaiso? What was he doing in town? What did he intend to do while in town?

Correa responded with tranquility: His mission as parish priest was noble, and his intentions were peaceful.

As for Arroyo, he simply explained that his mission as vicar was to help the parish priest in the exercise of his divine ministry.

When questioning finished, Ortiz ordered, “Get ready, because I’m going to take you to Zacatecas, to put you in prison for being seditious. Do you have something to go in?”

“No sir,” they answered.

“Well, you will go by foot,” he said, instructing them to return to the rectory to prepare for the journey.

“As you like, my general,” Correa answered as the two priests left.

Ortiz next approached Vicente Rodarte, Pascual R. Padilla and Lucilo J. Caldera, three imprisoned acejotaemeros – militant members of the ACJM, the Asociación Católica de la Juventud Mexicana (the Catholic Association of Mexican Youth) – who had worked zealously to gather signatures for the local Valparaiso group, established by Arroyo, on August 9, 1925. Their success had infuriated Ortiz, who had had them locked up.

This article appears in the December 15th Remnant Newspaper.

Don't miss the rest – Subscribe today!

The general asked Caldera, president of the local ACJM, “Do you believe in Catholicism?”

“Yes, sir,” Caldera answered.

“So, you believe that if I killed you right now that you would go to Heaven?”

“I believe so, with God’s help,” answered Caldera, as Ortiz walked away, disgusted.

After learning about the arrest of the two priests and the three acejotaemeros, the outraged townsfolk of Valparaiso decided to make sure that the political prisoners would not be transported out of town and out of sight. A commission of church women rushed over to the local Military Operation Headquarters and demanded to speak with Ortiz. When confronted, he vociferously spewed anti-Catholic views, especially maligning the priests, describing them as immoral, citing that as the reason why they were to be transported immediately to Zacatecas City.

But the faithful would be neither daunted nor deterred.

The day after the arrests, the townsfolk, many armed, arrived early in the morning at Ortiz’s headquarters with plans to thwart or, even, assault anyone who attempted to transfer the five soldiers of Christ. Faced with the threatening attitude of the religious mob, minutes before sitting down to eat his already prepared breakfast, the pusillanimous general fled, at 7 a.m., for Zacatecas, accompanied by 15 soldiers, who all would have been attacked and killed if Arroyo had not calmed the riotous crowd.

Relentless, the delegate of Catholic women hounded Ortiz. They pursued him, traveling nearly 100 miles to Zacatecas City to confront the sadistic general and to force him to soften his hatred for the priests, as well as the young men who had been released from jail after the escape of the general and his men. Cursing at them, the revolutionary demanded that they deliver the five Catholic men to him. Or else.

Before leaving the city, the women met with the interim governor, Leonardo Resendiz Davila. His suggestion: the wanted men should meet with him first, to give him an opportunity to calm Ortiz. So, on March 8, when the women arrived back in Valparaiso, they informed Correa that he, his vicar and the three acejotaemeros had to report to the Military Operation Headquarters, in Zacatecas City, but first they should speak with the interim governor.

Correa was very familiar with the capital city, for it was there, in 1881, he entered the Conciliar Seminary of the Purísima, where he received, on August 20, 1893, the Sacrament of Holy Orders. Years later, after the eruption of the Mexican Revolution, on November 20, 1910, the revolutionaries grabbed control of the country and began seizing Catholic property, including the seminary, stolen from the Church without compensation. Turned into a barracks and prison, it would eventually house a museum named after Socialist Manuel Felguérez.

Although very few of the townsfolk approved that the men should go, most demanded that they should not.

But following orders from authorities, the five Catholic men left Valparaiso that night and arrived in Zacatecas City the next morning at 10. Directly, they went to the gubernatorial palace, where they found the interim governor, who scolded them for getting off too close to the Military Operation Headquarters, because Ortiz was waiting for them. During the meeting, he agreed that they were not criminals, but, nonetheless, the Christophobic general wanted them dead. He had an idea: Ortiz may soon permanently leave the city, so they should go into hiding until he left.

The five sought refuge in San Jose Hospital, where the R.M. Rafael de las Minimas – a blood sister of the priest – served her mission. But the next day, at 10 a.m., they received an urgent message from the interim governor: Report to Ortiz at his private residence. Immediately.

Before meeting with the general, they visited Bishop Ignacio Placencia y Moreira (1867-1951), who encouraged them, but warned them that they would suffer for Christ. The bishop blessed them, and they left, arriving at Ortiz’s residence, at noon.

“Why hadn’t you come?” Ortiz asked the priests.

“For lack of money,” Correa answered.

“Yes! For lack of money! Poor Mexican clergy, as poor as this!” he taunted and then turned to the acejotaemeros: “And you, why hadn’t you come?”

“Because you ordered us to present ourselves together with the priests,” Caldera explained.

Calling his secretary, Ortiz ordered that the five Catholics be handed over to the Public Ministry and charged with sedition, based on the manifesto and the circular of the general committee of the ACJM.

“This pair of priests is deceiving these stupid young men. By means of and in accordance with the likes of the bishop, they are preparing a revolution,” Ortiz declared, telling guards: “While the order is being made, these sons of whores must be put in a cell.”

Escorted to a filthy room, at 12:45 p.m., on March 10, the prisoners immediately prayed the rosary and then settled down into the squalor. After locked up for six days, on March 16, they were ordered to be immediately released, after a district judge declared that the accused had committed no crime.

Outraged at the juridical loss, the humiliated Ortiz vowed revenge on Correa, whom he blamed as the puppet master pulling the strings of the acejotaemeros, responsible for all that they did.

Released from custody, Correa and Arroyo sought to meet again with the bishop of Zacatecas at the episcopal palace; however, he had been evicted, following the nationalization of the building, stolen by government forces without restitution. Eventually, they located him at the home of Fernando Lejeune, where the bishop joyfully greeted and embraced them.

Listening to the ordeals that his priests had experienced and endured, and learning that Ortiz had threatened death if they returned to their parish in Valparaiso, the bishop informed them that, because of the impending danger, they were free either to return or not to return. And if they did not return, he decided that he would not send other priests, because the risk of execution was just too great.

Following some discussion, prayer and contemplation, the priests decided to entrust their fate to God and to return to their parishioners, the faithful, alone without spiritual guidance, suffering under the brutal fist of the Socialist regime. The following morning, March 17, the Feast of Saint Patrick, the priests offered their daily Masses, ate breakfast and then departed for Valparaiso, at 8:30 a.m., without visiting anyone else to avoid any new dangers.

Along the way, they were seen by parishioners, who spread the good news. As soon as the two priests arrived in town, they were greeted with flowers, tolling church bells and cheers from faithful crying with joy. Upon their approach to the front of the church, everyone rushed forward to hug the men. And once inside, Correa prayed the rosary and preached about charity – love of one’s fellow man – toward enemies.

When the acejotaemeros arrived, they kneeled before Correa and requested a blessing from the modern-day Miles Christianus, who wielded weapons of kindness and understanding. Because of their brief imprisonment, the ACJM – defender of the principles, freedoms and rights of the Church – gained many recruits, which resulted in an avalanche of signatures. The army of young Catholics also posted copies of the foundation’s manifesto and the program of the League on walls along the streets, for which some were arrested, as per the orders of Ortiz. But having committed no punishable crime, they were soon released, much to the displeasure of the general, whose uncharitable hatred for Correa festered.

On June 14, 1926, the regime signed into law – set to take effect on July 31 – the anti-Catholic legislation, the Law for Reforming the Penal Code, commonly referred to as Calles Law, because it was an executive decree from Calles, the Mexican president, who, basically, outlawed Catholicism.

Subsequently, the Mexican bishops ordered, on July 25, 1926, that all churches be closed to the Sacraments “from July 31 of this year, until we decide otherwise.” In part, the episcopal letter stated:

“In the impossibility of continuing to exercise the Sacred Ministry according to the conditions imposed by the aforementioned Decree, after having consulted with Our Most Holy Father, His Holiness Pius XI [Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (1857-1939)], and obtained his approval, we order that, from July 31 of this year, until we decide otherwise, the public worship that requires the intervention of the priest will be suspended in all the temples of the Republic.

“We warn you, beloved children, that it is not a matter of imposing the very serious penalty of the interdict, but rather using the only means that we currently have to express our disagreement with the anti-religious articles of the Constitution and the laws that sanction them.

“The temples will not be closed, so that the faithful can continue to pray in them. The priests in charge of them will withdraw from them to exempt themselves from the penalties imposed by the Executive Decree, therefore being exempt from giving the notice required by law.

“We leave the temples in the care of the faithful, and we are sure that they will conserve with total care the sanctuaries that they inherited from their elders, or those at the cost of sacrifices they built and consecrated themselves to worship God.”

Preparations began.

To spiritually arm the acejotaemeros for the impending spiritual battles, Correa offered a series of spiritual exercises, first published, in 1548, by the founder of the Order of Jesus, Saint Ignatius of Loyola (Iñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola, 1491-1556), based on the Spaniard’s personal meditations, contemplations and prayers.

In the final hours, on the final day, Friday, July 30, services were held in the 12,000 Roman Catholic churches throughout Mexico. Priests offered continuous Masses every 30 minutes to parishioners, elbow to elbow, clamoring for the Sacraments in standing-room-only facilities until nightfall, when the government grabbed control of church annexes and sealed up ecclesiastical treasures, in accordance with the religious regulations that were to become effective the next day, July 31. To add insult to injury, Mexican President Calles gave the Pope’s representative, Monsignor Tito Crespi, 24 hours to leave Mexico, all reported by the New York Times.

On that day, Correa, with a heavy heart, asked Arroyo to prepare the parish church in Valparaiso, while he, himself, prepared the church in Lobatos, to make ready for the in-church boycott of the seven Sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation, Holy Eucharist, Penance, Extreme Unction, Holy Orders and Matrimony.

Undeterred, even though there were no longer Sacraments offered inside the government-controlled churches, the shepherds continued to tend to their flocks, offering the Sacraments outside churches, in private, in homes, barns, fields, wherever possible.

Still, the hierarchy continued their battle, doing their best for individual justice against an unjust government. On behalf of all Mexican archbishops and bishops, Archbishop Jose Mora y del Rio (1854-1928) and Bishop Pascual Diaz y Barreto (1876-1936) presented, on September 6, 1926, a memorial request – a petition with a statement of facts – to the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house in the Congress of the Union, to remove the persecuting laws, the anticlerical provisions in the 1917 Constitution:

In exercise of the right to petition, guaranteed by Article 8 of the Constitution and in response to the invitation that the citizen President of the Republic has served to make us, we come to demand, on behalf of the Mexican Catholic people, the repeal of some provisions of the current General Constitution, and the reform of others, with the patriotic purpose of putting an end to the current religious conflict; to obtain for Mexican Catholics the freedom of their Church; to purge the Constitution of contradictory and unjust precepts that, on the one hand, declare that the State ignores the religious reality of our country, and, on the other, limit and organize it with slavery norms; and to agree, for the good of Mexico, the Constitutional Law and the postulates of Civilization.

As the ancient wisdom affirms sententiously: “There is no tyranny worse than that of bad laws,” and in the face of those that destroy religious freedom in Mexico, the strict duty of Catholics is to vigorously seek their repeal.

“May all Catholics,” says Pope Leo XIII [Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci, 1810-1903], “realize this well: To display their activity and use their influence to force governments to modify wicked laws devoid of wisdom, is to show a devotion to the Homeland, as intelligent as it is courageous...The respect that is due to the constituted Powers, could not prevent it, because...the Law has no value except insofar as it is a precept ordered according to reason and promulgated for the good common, by those who have received the deposit of authority for this purpose.”

What do we ask for? Neither tolerance nor complacency, much less privileges or favors. We demand freedom, but we demand only freedom, and for all religions.

Modern society has been founded on freedom; for freedom so many institutions have been destroyed and so much blood has been spread; a regime of exception against religions would be nothing but the denial of that freedom.

It is enough for the Church to remain within its limits for it to be obliged, in justice, to respect it. And those limits have been specified by Jesus Christ himself on two memorable occasions.

When asked whether the tax should be paid, he responds: “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s”; and the day when two young people approach him, in the middle of the crowd, and one of them begs him: “Master, speak to my brother that he divide the inheritance with me.” “Man,” Jesus responds, “who hath appointed me judge or divider over you?” To point out that if He did not come to earth to resolve material conflicts of interest, He did come to kindle the moral light in consciences, Christ adds: “Take heed, and beware of all covetousness.”

This and no other is the attitude of the Church to the State.

For this reason, civil society has the right to dictate laws, in its domain, dispensing with all religious intervention, but without invading the religious field.

For this reason, our requests are reduced to ensuring religious freedom, which includes: freedom of education, without which freedom of thought and freedom of speech are a myth; the freedom of association that allows men, subject to the religious vow, the full realization on this earth, of “life in God” and living in community which, as the sacred text says, is nothing but a “provocation to charity and to good works”; freedom of worship, which guarantees the independent organization of the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy and the religious Government, as well as the performance of rites, without restrictions or oppressions; and the freedom to possess what is essential for the fulfillment of the religious and charitable purposes of the Church.

That these reforms are a national requirement, it is eloquently revealed by the initiatives of Don Jose Venustiano Carranza de la Garza [1859-1920] for the modification of Articles 3 and 130 of the Constitution, made by the Chief of the Revolution, when it had not been two years since the Constitution had been promulgated and the echoes of the armed conflict had not yet been silenced.

Note that taking into account the circumstances of the medium and time, when proposing constitutional amendments, we do not extreme our requests as far as we could with justice, and we do nothing but reproduce the text of the Reform Legislation or the original text of the Constitution of ’57.

What less could we ask for in Article 3, than sincere freedom of education? There are nations, like Belgium, Holland, England and others, where without distinction of creeds, the State supports every school. We do not ask but freedom to open our schools, supported by Catholics.

The modification requested for Article 3 only contains some variation of the wording of the 1857 original, to clarify its meaning.

Article 24 is mitigated in the sense that in extraordinary cases and in agreement with the authorities, that the true need of Catholics be satisfied when they do not fit in the enclosures of the temples when celebrating some act of worship.

The reform of Section III of Article 27 is the least that can be requested in matters of property, since we do not ask for other recognized powers from charitable associations.

The modification of Paragraph 1 of Article 130 was indispensable for it to correspond to the postulate of independence between the Church and the State.

The other modifications and deletions are imposed from the moment in which the Constitution wants to be based on a regime of true freedom and sincere separation between the Church and the State.

Note also that with our requests we do not in the least hinder anything that is about the aspirations of nationalism and redemption of the worker, whose “undeserved suffering” forced Leo XIII to become the “Pontiff of the Workers.”

Why should we view with revulsion, or even with antipathy, the noble impulse aimed at the full realization of the Mexican Homeland, which is ours, much loved, or the laudable purpose of improving the condition of the proletariat of the fields and the cities, when, as Jean-Baptiste Henri-Dominique Lacordaire [1802-61] proclaimed, “It is God, Himself, who moves in societies to which an effort of renewal requests”?

No; what we reject is the slavery of the Church, which is nothing other than the slavery of Catholics in the exercise of their religion, slavery that brings with it, sooner or later, all the others.

With the current texts of the Constitution, it happens that, unlike in other times when the protectors of the Church (Constantine, Louis XIV, in general, the royal governments) wanted to be, at the same time, Her pontiffs; today, they want to be Her persecutors.

That is why we protest and ask that “the Church be allowed to turn freely to God, through the realities of this world.”

That the French thinker Emile Faguet [1847-1916], in no way, may be suspected of bias in favor of dares, he concludes in his book “The Anticlericalism” [1906] with these sensible and fruitful words:

“It [the political party of moderates] would be patriotic and liberal, and liberal by patriotism. It would be convinced of this truth that all peoples have an interest, not only in eliminating out of the city, not to destroy, thus eliminating, any of the national forces, but also that it has an interest in converting into national forces all the elements of intellectual and moral energy that are in him.

“Now, given the infinite diversity of temperaments, characters, tendencies, beliefs, opinions and ideas that exist in the modern world, the homeland can only be loved by all if it admits this diversity, that is, if it respects and promotes freedom; and the country can only be loved by a few, which is a terrible danger, if, in this diversity of opinions, it takes one to make it its own and to impose it.”

No political party, much less a religion, can be legitimately suppressed with laws of persecution. The only worthy means to achieve this is through the propaganda of ideas, peaceful but loyal, leaving the adversary to enjoy the same circumstances and means.

Social balance, as Jean-Gabriel de Tarde [1843-1904] advocated, tends to rest on a maximum of love and a minimum of hatred. Give satisfaction to Catholic yearnings, sincerely accepting a postulate that can bring peace to nations that lack unity in religion, the postulate of independence between Church and State, with all its natural and logical consequences, and you will erase divisions and quench grudges in the Mexican family. Only in this way can the moral unity of the country be achieved in freedom and the realization of democratic government.

Our requests are sanctioned in advance by the classic formula that synthesizes all the norms of every government that wants to fulfill its own purpose: “Provide society with the greatest sum of well-being, with the shortest way to freedom”; these same petitions are sanctioned by all the laws of civilized peoples, and they will finally bring about the immense benefit of the tranquility of consciences, because as long as all these provisions are not repealed, as we ask, the religious question will remain agitated or latent.

Let’s read in Isocrates [436-338 B.C.]: “The condition of a good government is not that the porticoes are covered with decrees; it is that justice dwells in the soul of men.”

And on the other hand, among the beautiful and noble currencies of the States of the American Union, there is this one, which belongs to the state of South Dakota, and whose inspiration is entirely Christian: “Under God, the people rule.”

The President of the United States, in his letter to the Cardinal Legate of the Pope at the Eucharistic Congress in Chicago, left these words, very worth remembering on this occasion: “If our country has achieved any political success, if our people are addicted to the Constitution, it is because our institutions are in harmony with their religious beliefs.”

What we ask is that the constitutional articles be drafted as follows:

Article 3. Teaching is free. The one taught in official establishments will be subject to the conditions established by law.

Article 5. The State may not allow any contract, pact or agreement to be put into effect that has as its object the impairment, loss or irrevocable sacrifice of human freedom, whether due to work or education, nor may it establish any sanction, civil or criminal, to force the fulfillment of religious vows.

Article 24. Every man is free to profess the religious belief that pleases him the most and to practice the ceremonies, devotions or acts of the respective cult, ordinarily in the temples or in his private home, provided that they do not constitute a crime or offense punishable by the law.

The Subsection that says: All religious acts of public worship must be held precisely within the temples, which will always be under the supervision of the authority.

Article 27. Paragraph 7, Section II is deleted.

Section III should read as follows:

III. Public or private charitable institutions, whose objective is to help the needy, scientific research, the dissemination of education or any other lawful object, may not acquire more goods than those essential for their purpose, immediately or indirectly intended for it; but they will be able to acquire, have and administer capital taxes on real estate, provided that the places of taxation do not exceed 10 years.

Religious associations called churches, whatever their creed, will be subject to the same property regime as charitable institutions in terms of temples destined for public worship, their annexes, bishoprics, cural houses, seminaries, asylums, orphanages, hospitals, schools and any other building of religious associations, destined to the purpose of the same.

Article 130. Paragraph 1 shall be drawn up in the following terms:

It corresponds to the Federal Powers to exercise in matters related to the various cults and as regards public order, the intervention determined by the laws. The other authorities will act as auxiliaries to the Federation.

Paragraph 5 says: “The law does not recognize any presence to groups called churches,” will be in the following terms: “The State and religious associations and groups called Churches are independent from each other.”

Churches are free to organize hierarchically, as they see fit; but this organization does not produce more legal effects before the State that of giving presence to their superiors, in each locality, for the exercise of the rights recognized in Section III of Article 27.

Everything else is suppressed.

Transitory: Temples intended for public worship, bishoprics, cural houses, seminaries, asylums or colleges of religious associations, convents or any other building that, according to Subsection II of Paragraph 7 of Article 27 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1917, passed to the domain of the nation, they return to the domain and property of the respective religious associations.

On behalf of all the Archbishops and Bishops of the Mexican Republic:

President of the Episcopal Committee: Archbishop Jose Mora y del Rio [1854-192];

Secretary: Bishop Pascual Diaz y Barreto [1876-1936].

But the laws remained intact. Persecution continued. And Mexico, a Catholic country, devolved into a modern-day catacomb.

Christians endured tremendous hardship under the regime that pushed Socialism, an ideology embraced by sociopaths – those with antisocial personality disorders, a mental condition with symptoms such as the infliction of physical and psychological violence upon others, without remorse; a total disregard for laws and of the implicit, unwritten social contract between humans; a complete lack of empathy for other living creatures; and the exhibition of extreme arrogance; to list just a few.

For the next few months, Correa suffered a great deal, always on the move, traveling by donkey or by foot from hut to ranch to hacienda to offer the Unbloodied Sacrifice of Calvary and the Sacraments, all in secret. Sometimes sleeping in mountain caves, other times in open fields, often hungry, he always continued his pastoral work, toting a knapsack, which protected and safely hid his priestly vestments and the Blessed Sacrament.

To avoid authorities, he dressed as a peasant, for it was illegal to wear religious garb, according to the newly enacted Article 18 of Calles Law: “Outside of the temples, neither the ministers of cults, nor the individuals of either sex who profess them, may wear special costumes or distinctive features that characterize them, under the governmental penalty of 500 pesos fine, or, failing that, arrest that never exceeds 15 days. In case of recidivism, the penalty of a major arrest and a second-class fine will be imposed.”

Always, his enemies, the authorities, stalked him. Although his parishioners begged him to secrete himself away and hide, he gently refused and steadfastly continued his God-given vocation, his mission, smiling, trying to convince others that even though his hour was not far away, it had not yet arrived.

But then, on Sunday, January 30, 1927, Correa was approached by a peasant who explained that his critically ill mother, confined to her bed, requested a priest, for Last Rites, the Sacrament of Extreme Unction. Without thinking of the possible peril, he readily agreed and prepared to hear her Confession and offer her Holy Communion.

Immediately, he informed Jose Maria Miranda, dueño of the Hacienda de San Jose de Sauceda, a great estate where Correa had been staying as a guest since December 23, 1926. After requesting to go along, the two climbed aboard a four-wheel boguesito – a small cart drawn by mules – and headed out. As they traveled down the mesa of San Pablo, Miranda noticed a very thick dust cloud in the distance.

“It seems to me that this is a troop that is coming,” he said, suggesting that they turn around or hide somewhere.

But Correa disagreed, “No. Maybe they already spotted us,” and convinced Miranda that if they turned around, it would attract unwanted attention and cause suspicion.

Correa grabbed the reins and posed as Miranda’s employee.

Major Jose Contreras headed the column of dust-covered cavalry soldiers riding through the cloud of dirt kicked up by their horses. Four days earlier, on January 26, while leading the Callista troops against the Cristeros, he suffered a major loss in Huejuquilla, severely beaten by General Pedro Quintanar Zamora, head of Cristero Operations in the state of Zacatecas. The battle occurred after Quintanar returned from the uprising in Chalchihuites to be with his family in Huejuquilla.

Unlike Contreras, Quintanar was not a professional military man. A devout Catholic rancher, he had taken up arms and swore to avenge the horrific executions of the Chalchihuites martyrs, 4 devout Catholics (1 priest, 3 laymen), on August 15, 1926, at El Puerto de Santa Teresa, now known as Los Lugares Santos – one of the first mass murders in the Cristiada, the Cristero War. (See: https://remnantnewspaper.com/web/index.php/articles/item/5422-catholic-heroes-cristero-war-executions)

Stung by the military loss to a band of half-starved, ill-equipped religious fanatics, Contreras agonized over the defeat. Upon his retreat, he verbally assaulted Catholics he met along the way and ordered that the inscription Viva Cristo Rey! be removed from all doors. Scofflaws would most certainly face harsh penalties. And adopting the opinion of Ortiz, his boss, Contreras blamed one person as the mastermind behind the Cristero victory under Christophilic Quintanar. That person was another Christophile: the parish priest of Valparaiso: Correa.

In the boguesito, before too long, Correa and Miranda passed by the line of saddle-weary soldiers riding from Huejuquilla, guided through the region by Jose Encarnación Salas, a despised agrarista who favored agrarian policies based on the Communist Bolshevik model. He tipped off officials that the boguesito carried the owner of the sprawling San Jose estate and a priest from Valparaiso.

Contreras sent one of his men, who rode up to the boguesito.

“Where is the padrecito going to say Mass?” questioned the officer – using the diminutive “padrecito” to demean Correa as a “little priest” – as he took the opportunity and the liberty to reach into the priest’s bag and pull out the “Parish Manual,” with the name: “Mateo Correa.”

“He is my employee at the hacienda,” Miranda said of Correa to the officer, who already knew who the two were.

Soldiers conducted a search the boguesito. They found aboard: a small flask of holy oil, a bag of corporals, a paten and an altar linen. Fortunately, they missed the treasured reliquary with a Holy Host – in which the risen, sacrificial Lamb was present.

“Turn around,” the officer ordered. It was around 12:30 in the early afternoon.

“Please, let us continue to San Antonio, because we have arranged to dine with Don Eugenio Moncalea,” Miranda fibbed, trying to extricate himself and the priest from the predicament.

“That cannot be. You will have to go with us, because we are going to spend the night at your hacienda, and you have to give us accommodations. Go as you see fit: behind or in front of the column,” they were told.

With the intention of arriving back at the hacienda first to safely return the Host back in the private chapel’s tabernacle and avoid a desecration, they chose to advance before. Correa quickly turned the boguesito around, snapped the reins, and the mules kicked off for the estate. With only seconds to spare, they arrived before the head of the procession appeared.

However, the soldiers did not rest at the hacienda, for they were scheduled to arrive in Fresnillo. Correa and Miranda received orders to start up a hacienda van and to drive it the 60 or so miles to the city, near the pilgrimage site of the Holy Infant of Atocha, a much-revered image of a Child Pilgrim, believed to be the embodiment of Christ, who miraculously fed imprisoned men enslaved by Muslims, who then-ruled much of the 13th-century Iberian Peninsula.

That same day, Sunday, they arrived, under guard, in Fresnillo at 5 in the afternoon. Handed over to the Police Inspection warden, Correa and Miranda were shuffled around from cell to cell among the prison community of hardened criminals.

“It seems we are in the parish,” taunted one of their cellmates, greeted with laughter by his fellow miscreants.

While in the Fresnillo Penitentiary, Correa wrote to his sisters the following short-yet-profound epistle: “Sisters: It is time to suffer for Jesus Christ, who died for us. Have courage, and inquire about your brother who blesses you and entrusts you to Jesus through Mary. Mateo Correa.” Received by Guadalupe Correa Magallanes, as soon as she read the letter, she traveled to speak to Ortiz to free her only brother, but the general refused, falsely claiming that the priest had been bringing rebels from Huejuquilla.

Tuesday, February 1, at 4 in the afternoon, Correa and Miranda were escorted to a train station, where they waited. At 6:30 p.m., they watched as Ortiz’s soldiers slowly arrived and loaded their horses into four cages on the railcars. At 11 that night, a military train rolled into the station, to which the prisoners’ railcar was coupled, and finally departed. Without protection from the elements, Correa and Miranda endured hours of drizzly weather, stung with a constant, icy wind.

Wednesday, February 2, the train slowed to a stop in the Cañitas station at 4 in the morning. After a three-hour wait, they continued to the City of Durango and finally pulled into the station at 9:30 that night, when the troop disembarked and unloaded their horses. But the prisoners remained in their van, where they attempted to sleep in the cold, damp, cramped compartment.

Thursday, February 3, around 6 a.m., the priest and his companion were escorted to a corral on the outskirts of Durango, where the major’s troop was housed. After three hours, they continued to Captain Aguilar’s barracks and waited another two hours. While biding his time, Correa slipped out of the van and eavesdropped on a conversation, during which he heard the captain telling guards that they were to execute, by gunshot, Correa and Miranda and were to “do a good job of it.”

Returning to the van, deeply shaken, he told Miranda, “Who knows how it will go for us.”

At that time, Contreras arrived at the corral with another officer and spoke with Captain Aguilar. Subsequently, the two prisoners were escorted to Durango City Operation Headquarters, a former seminary and locked in a cell. Halfway up the wall, three windows let the sunlight seep through, the only light in the darkness that enveloped the men. Two prisoners were already there, and two more soon arrived.

Kind to his fellow inmates, Correa shared a few oranges he had and offered advice that they should accept their fate and patiently suffer in prison, which comforted the men, who, as night fell, made a bed for the 60-year-old priest with some desks from an adjoining room. Appreciative of the gesture, he expressed his gratitude to everyone.

Friday, February 4, officers entered the cell for roll call at 7 a.m. and complained that the lazy inmates had not cleaned their filthy area. Correa requested a broom from the corporal and busied himself, sweeping here and there at the dust and debris, refusing to relinquish his cleaning tool until every speck had floated away. During lunch, he shared his oranges with the others and then gave thanks with his fellow inmates before lying down for a nap at noon. He woke lighthearted, and, although at times his mood temporarily darkened with worry, he joked, played charades and shared riddles with the prisoners, trying to entertain them. At 6:30 that evening, dinnertime, he only drank coffee and gave his food to the others, suggesting they give thanks and pray the rosary, followed by the Grand Silence and sleep.

Saturday, February 5, Correa woke up very happy around 8:45 that morning and prayed the Divine Office, after which he announced to Miranda, “Today is the day of Saint Philip of Jesus, Mexican martyr. God help us, Don Pepe!” repeating the petition several times that day when worry overcame him.

Saint Philip (1572-97), the patron saint of Mexico City, was the first Mexican saint. When the ship he was aboard, in 1597, traveling from the Philippines to Mexico, crashed upon the rocks along the shore of Japan, he and others were falsely accused of preparing the way for foreign soldiers to take over the Land of the Rising Sun. Their captors cut off their ears, marched them through the streets of Kyoto, transported them to Nagasaki and forced them up the Mount of Martyrs, where they were hanged from crosses and pierced with spears.

Later in the day, at 5 in the afternoon, the duty sergeant entered the cell to give three oranges, a cake and $1.50 in silver donated by Catholic women to the thankful priest. At 7:30 p.m., dinner arrived, and, when finished, Correa prayed the rosary by himself, after which he chatted with two others – Jacinto Marrufo, Emilio Valdez— sitting around Miranda’s bed.

Around 8 p.m., the sergeant of the guard entered the cell and ordered, “Mateo Correa, fix your things, because General Ortiz wants to speak with you.”

The guard surprised everyone. Caught off guard, a shaken Correa rose and asked Miranda, “Should I take my things?”

“Yes,” Miranda answered, thinking that the priest was possibly going to be transferred to another cell.

To Marrufo, the priest said nervously, “Give me the address of your house, just in case something is offered to me, and to give you news of me.”

“Tercera de Ricardo Castro Number 12, Colonia Obrera,” Marrufo answered.

Before leaving, Correa walked over to say goodbye to Miranda, who kneeled to receive a final blessing from the priest.

“Trust in God,” Correa advised and then walked out of the cell.

That night, his cellmates waited for him to return. The wait, excruciating.

Sunday, February 6, the next morning, they still waited.

When guards arrived to take roll call, called out Correa’s name and no one answered, one of them said, “That man is now free.”

Alarmed at the comment, Miranda took the guard by the arm and asked, “Captain, I beg you, please, tell me the truth. Where is the priest? Have they placed him in some other department, or has something happened to him?”

“No, the general sent for him last night,” he answered.

Frightened, Miranda continued to wait, and wait. Days later, he kneeled to venerate the martyr after learning the truth about his friend’s fate:

On the night of February 5, 1927, after Correa was removed from his jail cell in the Durango Military Operation Headquarters, he was escorted to Ortiz.

“First,” Ortiz told him, “You are going to confess those rebel bandits who you see there and who are going to be shot immediately. Then we will see what to do with you.”

Knowing that his hour was not far away, but not knowing if it had arrived, Correa patiently and courageously listened to the confessions of the prisoners, Cristeros taken captive while fighting to defend their faith. An alter Christus, he absolved the penitents of their sins and encouraged them to die well.

When finished, he was confronted by Ortiz: “Now, are you going to reveal to me what those bandits have just told you?”

“I will never do it,” Correa answered, unwilling to break the Seal of Confession, the absolute duty of priests to never reveal anything heard during confession.

“Whatever.” the general replied irritably. “I’m going to have you shot immediately.”

“You can do it, but you are aware that a priest must keep the secret of confession. I am ready to die,” Correa answered, prepared to die in odium fidei.

Between 4 and 5 in the morning, Sunday, February 6, 1927, Correa was removed from the prison and placed in a car that sped off, stopping about half a mile from the Durango Municipal Cemetery. Ordered out, the ordinary priest in extraordinary circumstances was promptly executed, his body dumped, abandoned in a field.

His corpse was discovered, on February 8, by the Durango Police Inspection, and Agustin Martinez – brother of Jose Maria Martinez – was ordered by the Police Inspection to relay the findings to Operation Headquarters, where he reported to Ortiz, who answered with bizarre responses as one mentally deficient, emotionally defective and spiritually demonic.

“Sir, I just found a corpse,” he told Ortiz.

“What do you want with that?” Ortiz answered.

“Sir, the Inspection ordered me to come and report.”

“Go out, and eat it,” Ortiz said.

“I am not used to eating human flesh,” Martinez answered. “If I come to warn you, it is because I am ordered to do so, and because it is my duty.”

“You can now retire,” Ortiz said.

The following day, soldiers buried Correa’s body where it had been found.

Subsequently, family and faithful searching for the priest found the recently shoveled mound of earth, his freshly dug grave. Nearby, they noticed bloodstains and clumps of bloodied hair on stones, over which they surmised that his body must have been dragged. Nearby, they also found his hat, a piece of scarf, and a pistol cap. His remains lay undisturbed until the following year, when his corpse was exhumed, transferred and laid to rest in the Durango Municipal Cemetery, on May 8, 1928.

On November 22, 1992, Pope John Paul II beatified the martyr and later canonized him, in 2000, on May 21, the Feast Day of Saint Mateo Correa Magallanes.

____________

Miscellanea and facts were pulled from the following: “Los Martires de Cristo Rey,” by Andres Barquin y Ruiz, with prologue by the Most Reverend Jose de Jesus Manriquez y Zarate, Bishop of Huejutla, 1937; and “Los Martires Mexicanos: El Martirologio Católico de Nuestros Días, by Joaquin Cardoso, 1958.

Theresa Marie Moreau, an award-winning reporter, is the author of “Martyrs in Red China”; “An Unbelievable Life: 29 Years in Laogai”; “Misery & Virtue”; “Blood of the Martyrs: Trappist Monks in Communist China”; and the forthcoming “Cristero War: Mexican Martyrs.”