|

In a previous article, I argued briefly that, despite

the common aesthetic problems of Novus Ordo

worship-style, it was not in the best interest of

traditionalists to focus on these deficiencies, but to

instead focus on the problematic nature of the new

prayers. Let me briefly say a bit more about this here. In a previous article, I argued briefly that, despite

the common aesthetic problems of Novus Ordo

worship-style, it was not in the best interest of

traditionalists to focus on these deficiencies, but to

instead focus on the problematic nature of the new

prayers. Let me briefly say a bit more about this here.

I know a Catholic fellow who, while perfectly nice and

polite, I can’t seem to understand. He is pleasant

enough, to be sure. In fact, he is extremely generous

and kind.

But he doesn’t drink alcohol and he doesn’t follow

baseball. And for these reasons, I have a hard time

relating to him.

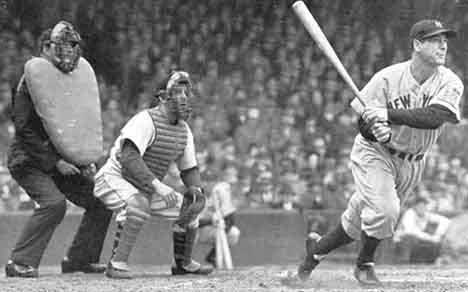

Actually, he doesn’t follow any sports. Of course, as

Catholics, we should be mostly concerned about his lack

of interest in God’s favored sport. I fear—for I’m

afraid to ask—that he doesn’t even really know the rules

of the game, let alone know any of the players, current

or past. I live in a city that has severe emotional

attachments to their baseball organizations; but as

baseball is God’s favorite game, this is one feature of

New York that I find virtuous, even heroically so. That

this colleague of mine does not participate in this

city-wide neurosis, I find disturbing.

As to the other of my colleague’s peculiar features, I

have it on good authority that he is neither recovering

from prior addictions nor reacting to other traumas: he

is simply averse to spirits of all sorts, and always has

been. As for me, while details are between me and my

confessor, I have no qualms in mentioning that I

appreciate a good pint in a pub. Wherever the Catholic

sun doth shine, indeed. How one would not like

this activity, I do not know.

So this acquaintance of mine: he baffles me. Now, not

drinking alcohol for no other reason than personal

preference, or worse yet, not loving baseball—these

are signs of social disorders in and of themselves, to

be sure. And where you find some disorders, you are

bound to find others. For our purposes, I should mention

one more peculiar quirk of this man. What I write next

should not surprise any of the readers of this fine

newspaper, given what I’ve written so far: this man, he

also cares rather little for the old mass or traditional

rubrics, and he rolls his eyes at those who agonize over

these adiaphora. This colleague of mine is perfectly

fine with versus populum and communion on (in?)

the hand, he cared not at all that—for example--the

recent beach party mass in Rio featured bikinied

‘ministers’ handing out hosts from plastic cups, and he

does not cry in horror at Paul VI Audience Hall or worse

yet, the wretched Domus Sanctae Marthae Chapel.

Moreover, as far I can tell, he seems content with the

hellishly awful music that infects his Paul VI Mass. The

music—dear God, the music—it seems to affect him

negatively not at all. Yes, he is a strange fellow.

Sneak Peek:

This article will be

featured in the next print edition

of The Remnant newspaper. Unlike this one, most

Remnant articles never appear on our website.

Click

here

to find out how you can become a subscriber

and never miss a single one of these excellent Remnant

articles.

I am not expert enough in the Ways of Man to say if his

frightening vision of the world is a product of barbaric

habituation, some sort of devilish, self-induced

beta-blocking, or a glitch in his DNA; but I’m quite

convinced that there is a connection between his

tee-totaling, his complete ignorance of and disinterest

in God’s favored game, and his ambivalence towards

liturgy. I haven’t done any sort of formal study, but

I’d be willing to bet that a large survey of the

American Catholic populace would reveal strong

connections between a disinterest in baseball and a

disinterest in good liturgy and good lager. This isn’t

to say that the best place to find those who appreciate

the Old Mass is the local pub on game night, but—no,

maybe that is the best place to find such people.

I don’t know: we should do a study (or just check the

pub and see, and while we’re there…).

This is all to say that we can speak not just of

conflicting visions of the good, but large divisions

over the nature of the beautiful. And these divisions

run deep. This makes sense, if one takes a rather

old-fashioned view of taste as something that

tracks, if ordered rightly, objectively beautiful

things. Those who have the virtue of good taste, argued

Aristotle, find (really) beautiful things beautiful.

Such a philosophy seems, prima facie, terribly

pretentious and elitist from our modern, egalitarian

perspective (and that Aristotle would include this

virtue in his ethical treatise, no less, makes us

gasp!). But once we get over our indignation, most are

resigned to admit that Aristotle is on to something

here. Indeed, even the utilitarians are happy to say,

along with John Stuart Mill, that there are higher

pleasures to be pursued, simply because we are humans

and not animals (I’ll leave it to the utilitarians to

figure out how Mill’s concession concerning the

insufficiency of the ‘satisfied pig’ doesn’t collapse

utilitarianism entirely). No, it seems perfectly correct

to speak of good taste and bad taste. And therefore it

seems perfectly correct—as terrible as this might

sound—to speak of the more refined tastes of those who

prefer certain liturgical rubrics over others.

But here is where our problem begins. Because forget

about bad liturgy for a second. Forget about communion

in the hand, songs about gathering, liturgical dancing,

and the barren wasteland of ‘ordinary time’. How, pray

tell, do you get someone who does not like baseball to

like it? I suppose you could answer: the same way that

you get someone to enjoy a good glass of wine. You get

them to acquire a taste for it.

Yes, acquisition and acclimation through habituation.

That’s the name of the game, to be sure. Aristotle is

right: proper habituation is everything. Assuming that

poor taste is not a result of faulty physiology, I

suppose we could get my colleague to like baseball by

dragging him to Yankee Stadium, in the same way that we

drag those at the bottom of Plato’s cave, kicking and

screaming, to the light.

But just as Plato’s cave dwellers have been habituated

to appreciate the shadows in their flickery darkness,

and just as they fastly flee back to the safety of the

darkness upon being dragged out by those in the know, my

baseball and beer-hating colleague will most certainly

be rather annoyed at my insistence that he must

accompany me once again to the afternoon game.

But drag him I must, one might argue.

And yes, the required tie-in to the Old Mass, can now be

briefly made, and some point about how the Old Mass

‘takes some getting used to’, and how this also requires

some acclimation by those not previously disposed to

such worship style, can be written. Of course. So

consider this here the requisite mentioning of this

point.

Very good. But enough about that. It is more important

to point out what a lousy state of affairs this is. For

the answer to our problems—habituation—has revealed a

troubling aspect of getting things right in the beauty

game. However successful this acclimating program for

our aesthetically-blind acquaintances might be, we

should note more importantly how, from the beginning, we

have recognized that there is simply no straightforward

appeal to reason available.

One cannot simply offer a written argument for the

beauty and grandeur of baseball, or Guinness, let alone

the Traditional Latin Mass. Believe me, I’ve tried with

my colleague regarding all three. It appears that it’s

habituation or nothing. If you do not see the

beauty of any of these things, the best I can do, given

my fortunate access to this ‘inside information’, is to

get you too to ‘try them’. I cannot present a PowerPoint

presentation for their aesthetic superiority (I’ve also

tried this), and expect anyone who isn’t already

convinced, to be convinced.

So enough about baseball and beer. If you do not see

the beauty of the Old Mass, of ad orientem, of the

Latin language, of Gregorian chant—if you do not

recognize the superiority of these forms of worship,

then nothing that anyone says about these

things will do any good. If someone has been poorly

habituated, then, as Aristotle rightly said, they will

see the ugly as beautiful, and the bad as good. Sadly, a

distorted sense of taste cannot be corrected by the

offering of a syllogism.

This isn’t to say that beauty isn’t rational. It’s

entirely rational, and therefore knowable. Beauty

supervenes on being, and being is intelligible. But not

all knowledge is built on a priori, self-evident

truths that can be found regardless of one’s lot in

life, simply by transcending the confines of a wrongly

encultured mind, and thinking upon things ‘purely’. To

think this is possible—this is one of the many myths of

the Enlightenment. Most certainly, there are deft

philosophical arguments for why certain things are

objectively beautiful and others are not (and many of

these arguments are right). Moreover, as the work of

Benedict XVI on liturgy attests, there are arguments

that connect good theology with good liturgy and proper

reverence and form. But Benedict does not proceed like

Euclid, by building up a large set of necessary truths

from initially posited self-evident principles. A

traditionalist cannot build up a logically air-tight

case for the insanity of communion in the hand.

Likewise, I cannot make an argument for the stupidity of

my colleague’s favorite hymn (you don’t want to know) in

such a way that reveals that he is in fact offering a

logical contradiction by disagreeing with me.

At the end of the day, after all arguments are made, and

all theological and philosophical matters unpacked and

explained, we still have to appeal to a proper vision of

reality in order to make our arguments for the

beautiful, and getting this proper vision takes some

real work on the part of the poorly trained. If one’s

eyes aren’t trained, then reading or arguing will only

do so much good.

So what does this mean? It means, among other things,

that if failure of a purely logical appeal to the

beautiful is impossible, then we should not be surprised

that so many in the world of the Novus Ordo simply can’t

see what traditionalists see, and we should not be

surprised, moreover, that Novus Ordo types get annoyed

at traditionalists constantly pointing out to them their

ridiculous music, their architectural disasters, and

their irreverent forms of worship. Traditionalists

cannot proceed by axioms, but neither can they hold up a

CD of Tomás

Luis de Victoria in one hand, pound their other hand on

the table, and declare, “If you’d just LISTEN to

this, you’d understand!” It’s not that easy.

This isn’t to say that we should cease trying to train

those who are amenable to being trained. And drag we

must our friends to the Old Mass. But in the meantime,

we can appeal to aspects of the Old Mass that require no

habituation or privileged vision to understand. There

are features of the Old Mass that are superior to the

New Mass, but that require no inside information to

grasp.

The prayers. The content of the Old Mass. If there is

any straightforward ‘empirical’ or strictly ‘scientific’

argument to be made, if there is any argument that does

not transgress the so-called fact/value divide, if there

is any appeal to the superiority of the Old Mass that

does not threaten the sensibilities of those who

actually like songs about gathering, it’s the

prayers themselves.

We do not need to properly habituate or reorient

anyone’s vision to see the problematic nature of the

prayers of the New Mass. We simply need to do a quick

compare and contrast. Whereas explicit references

to Catholic dogma saturate the collects, secrets, and

antiphons of the Old Mass, the same cannot be said of

the prayers in the New Mass. When it comes to the

content of the prayers, we do not need inside

information to understand the problem. In fact, one does

not even need to be Catholic to see the

differences in the prayers. One simply has to know what

Catholics teach regarding the Real Presence, the merits

of the saints, propitiation, and the like. Thus, to

focus on the worrying prayers of the New Mass is not to

make an appeal to a properly formed vision, nor is it

even to appeal to specifically Catholic

sensibilities. It’s simply to appeal to facts

about Catholic belief. Any Methodist could tell you, if

(you found one and) had him quickly compare the prayers

of any given Mass for any given day, that one Mass had

more Catholic-rich content than the other.

For this reason, focusing on content is the safest

strategy a traditionalist can take. There is no risk of

offending anyone when we simply focus on the fact that

these prayers do, and these prayers do not, reference

particular Catholic dogmas. It is to simply focus on

facts. Facts, as philosophers point out, do not offend.

Only values do. Moreover, to point out faulty content is

to focus on aspects of the New Mass that do not run the

risk of attacking faulty character. To focus on content

is not to criticize any one parishioner’s taste, and

more importantly, it is not to criticize any one priest.

After all, not only are priests overworked and

underpaid, but they can’t help what they are given to

work with. The prayers are what they are. It is not the

fault of any priest or any parishioner, nor is it a mark

of anyone’s poor taste, that the content of the New Mass

is what it is. Most importantly, to focus on content is

not to present yourself as superior in any way.

In my case in particular, this is quite important, as

such a self-presentation would be impossible.

I’ll probably never get my colleague to appreciate the

joys of a good glass of wine by demanding, again and

again, that he try it. I similarly have had no success

convincing him of the joys of baseball. But I should be

able to convince him of the superiority of the Old Mass,

simply by appealing to his knowledge of Catholicism, and

then showing him the differences in the content of the

prayers of the two Masses. Who knows: perhaps when he

sees the factual differences, he’ll start attending the

Old Mass, and this will start a process that will

properly habituate him, and rightly form his sense of

taste. Before you know it, he’ll be joining me for a

pint in the pub for the night’s game. |