Our teacher told us to turn to the students around us, shake their hands, and say, "Peace be with you." We started giggling as we did so, quite naturally I believe. She sternly scolded us, saying this was the Mass we were laughing at, the Pope wanted the change, and that we were being very disrespectful.

The sight was an education without words.

The episode, small as it was, set a template for the coming years. The New Mass was not just new in 1970, but remained so for years, changing in a process with no apparent end. And with each change, there was nothing to do or say: this was the Mass, the Pope wanted the change, and any complaint would be very disrespectful.

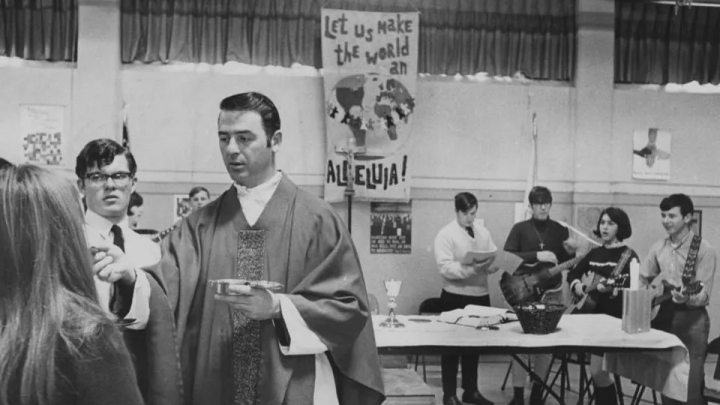

A part of the New Mass which had not changed much from the Traditional Mass, at least by 1970-1971, was the communion ritual. It was also the only part of Mass I had actually observed. Our church was packed in the late 1960s, and most of the time I was lost in a forest of taller folk as amplified words (in English by now) washed over me.

When it came to communion, however, I could see. Children who had not yet received First Communion did not approach the altar rail in those days. We stayed behind while adults, older kids, and babes in arms processed forward.

I watched intently as the long line of families decorously moved along. I saw them carefully kneel at the rail, while the priest solemnly moved back and forth administering communion, he alone touching the Eucharist. I noted the careful attention of the altar boy, in cassock and surplice, holding the paten lest a host drop.

It is impossible to exaggerate how deeply these observations touched me. Even now, I tear up as I write about it. The sight was an education without words.

Later, in our classroom preparations for First Communion, we were told about transubstantiation and the Real Presence. I felt intense joy upon hearing these terms. It was as though I already knew the truth, and that the words were giving flesh to a living belief.

This, then, was how I received First Communion in April 1971. I approached the altar rail, as so many Catholics had before. I knelt in reverent expectation as the priest placed the Blessed Sacrament on my tongue. I returned to the pew, feeling a comfort I had never known.

So how horrible it was when the initial changes to the New Mass focused precisely on the communion ritual. The first change was to receive communion standing. At some point in the mid-1970s, we were told to do so with admonitions about being a "mature people of God."

It was weird, I thought, that half the parish would move at the same time. I wondered where they went.

I remember standing in the communion line and glancing sideways at the now-unused altar rail. There was something strange about an abandoned liturgical fixture, as if the things which had surrounded it were no longer true. I knew better than to say anything, however.

Another change in the mid-1970s was that half my parish moved away. Well, not really, but that was how my youthful brain processed it. Whereas being "on time" for Mass in the late 1960s meant arriving 10 minutes early, or else we would sit on folding chairs in the vestibule and stare at the wall, we could now arrive as Mass was starting and sit anywhere we wanted. It was weird, I thought, that half the parish would move at the same time. I wondered where they went.

Not coincidentally, perhaps, the New Mass was promoted with increased intensity. The most common approach was to contrast the New Mass with the "Old Mass," as the Traditional Mass was uniformly called. In class, for example, we were told that in the Old Mass the priest prayed with his back to the people, which was bad, but in the New Mass he prayed facing the people, which was good. In the Old Mass the priest prayed in Latin, which was bad because no one understood it, but in the New Mass he prayed in English, which was good because everyone understood it. In the Old Mass the people did not participate, except by maybe praying a Rosary, which was bad, but in the New Mass everyone could participate, by carrying up the offertory gifts, for example, which was good.

The strategy was clearly, "Old Mass bad, New Mass good." I do not think the approach was limited to my parish because we were taught with commercially-prepared materials. One film strip in particular left a lasting mark.

Before going on, I'll describe what a "film strip" is for readers not experienced in the audio-visual medium. It is a ribbon of celluloid with translucent frames arrayed in line. The film strip is fed into a small projector and, at the same time, a vinyl record is started on a phonograph. The narrator's voice, and any other sounds on the record, are matched to the sequentially advanced frames. The projector operator knows to advance the frame each time a "beep" sounds from the phonograph.

The film strip in question was, like most of our materials, about the improvement of the New Mass over the Old Mass. The sequence of frames I remember began with a stylized painting of a priest praying the canon in the traditional way, from the congregation's perspective. The subsequent frames progressively panned out, making the priest and altar appear smaller and smaller. The narration went something like this:

"In the Old Mass, the priest prayed with his back to the people."

"Beep."

"Over time, the altar was moved further away."

"Beep."

"The Mass was now further . . ."

"Beep."

"And further . . ."

"Beep."

"And further from the people."

I am not kidding when I say this produced an intense panic in me. "They are taking the Mass away! They are taking the Mass away!" I recall saying to myself. I became convinced that the Old Mass was very, very bad. No amount of contrary information or experience in the coming decades could change my mind.

Somewhat later in the 1970s, we learned that lay people could now distribute communion. Like all changes to the communion ritual, this one disquieted me. I had no framework to evaluate it, however. No one had explained why only a priest should touch the Eucharist, so when our priest said lay people could distribute, who was I to argue? It didn't make me feel any better, however.

It was startling, however, to hear him growl: "A priest's hands aren't any better than anyone else's hands."

A married couple was chosen for the role, and the wife just happened to be short. Receiving from her, both standing and on the tongue, became difficult as I grew taller. She would voice a clicking sound when I appeared, a sort of "tsk," and then reach up on tip-toes as I leaned awkwardly forward. The angle of attack was all wrong, and I usually had half her hand on my tongue.

That was not very pleasant, so when a priest told us at the end of the 1970s that we could now receive in the hand, I was relieved. It was startling, however, to hear him growl: "A priest's hands aren't any better than anyone else's hands." I again didn't know what to think, because we hadn't learned differently. But it still didn't seem right. Almost nothing was sacred, or even stable, it appeared.

I nevertheless felt called to the priesthood and entered the seminary in the early-1980s. The liturgies were reverently celebrated, with seminarians serving and priests or deacons distributing communion. With a few exceptions, I do not remember having much of a problem with the New Mass in the seminary.

After discontinuing my studies and returning to parish life, however, the problems escalated substantially. The non-seminary version of the New Mass had continued to change. More lay people distributed communion, many of them women, more women served as lectors, and girls were serving at the altar.

I began to have difficulty making it through the service. The feminization of the liturgy was simply offensive—I know of no other way to put it. There were probably several factors.

First, the increased number of females in the sanctuary set a tone. The priest, intentionally or not, would often adjust his tone to fit. Emotion, sociability, and gentleness came to the fore, while rationality, order, and drive seemed to recede.

Second, improvements in technology increased the focus on the persons leading the ritual, as opposed to the ritual itself. I had always known electric lighting and sound amplification, but the equipment typically used in the 1960s was nothing like that available by the late 1980s. Focused spot lights, sensitive mobile microphones, reliable amplifiers, and clear, powerful speakers increased the ability of those leading the ritual to project themselves. The subjective tended to displace the objective, and the inversion struck me as feminine.

Third, I was older. I suppose that as a man matures, he feels he should take his place in society. The New Mass did not feel like such a place.

The feminization of the liturgy was simply offensive—I know of no other way to put it.

Underlying much of this was the ritual of the New Mass itself. The Mass was designed for "active participation," and as time when on, every avenue to that end was exploited. Almost anything was possible, it seemed, because events were controlled by the celebrant, who might even extemporize from the altar. Through posture, words, and tone, the New Mass was changing from a ritual into a show.

For readers thinking this had already occurred by 1972, I have so far described my home diocese. Wichita is a relatively conservative place, and the bishop from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, the Most Rev. David Maloney, kept the things on a comparatively even keel. Changes still happened, but we lagged behind.

Ironically, my response to all this was self-distraction. Lacking musical training and possessing modest vocal talent, I nevertheless joined a choir. I not only had friends there, but I could now focus on the music, thereby shielding myself from events in the sanctuary. "Is this a flat or sharp? I can never remember. And what about that step there—half or whole? I had better review this music some more."

My strategy was only partially successful, however, because the spirit of good humor in the sanctuary was met by the congregation. Talking increased significantly, especially before Mass. And the standards of dress kept falling, reaching even immodest levels. Another reason for a man to keep his eyes on his music books.

Church was frankly no longer a place I wanted to be. As I thought about it, I realized that while I had to go to Mass, I didn't have to like it. So this became a personal motto: "You have to go to Mass, but you don't have to like it."

I repeated the motto to myself many times during the week, whenever I thought of what was coming on Sunday. When I could no longer steel my will to attend, I prayed for the grace to do so. My prayers of petition eventually became constant, starting anew each week as I drove away from Sunday Mass.

I also noticed that I was experiencing painful depressions on Sunday afternoons. I will mention by way of explanation that I had left the seminary with a major depression. As my condition improved, I realized the symptoms were reappearing each Sunday after Mass. They typically resolved by evening, but I could do nothing to disrupt the pattern. It was as though the tide of depression had gone out and left these stubborn pools behind.

Whenever the liturgy became particularly effeminate, I would think: "They are trying to run everyone out of church except for women, boys, and old men."

In the mid-1990s, I looked around at Mass and realized there were almost no men my age. I saw old men and boys, and plenty of women, but only a few dutiful fathers, almost all wearing casual clothes and a look of pained endurance. I remember thinking that if other guys suffer at Mass as I do, their absence isn't surprising.

Whenever the liturgy became particularly effeminate, I would think: "They are trying to run everyone out of church except for women, boys, and old men." I started a ledger in my head of attendance by sex and age. I noticed in particular the lack of men I considered athletic. The absence was significant because I had moved to a university town in another diocese, the home of a Division I school in a major athletic conference. I knew those guys were out there.

I recalled an incident from my undergraduate days at the same university. The Catholic campus center mailed newsletters to the Catholic members of my fraternity. Most of these lay for days unclaimed on a table. When I examined the names, I was surprised to see among them some of the best athletes in the house. I didn't even know these guys were Catholic. I had never seen them at Mass.

I will relate two more experiences with the New Mass, both major crises. These require some background. The first because people might think my reaction silly, even ridiculous, and the second because the crisis was brought on not by a change in the Mass, but by a change in my thinking.

To explain the first crisis, I should say that as a boy I travelled quite a bit with my parents. Wherever we went, we made it to church on Sundays. I would walk in like I owned the place, genuflect before the Tabernacle, and sit in the pew, happy.

I was happy because I knew Jesus was there, and because I was Catholic. I would think of my Protestant friends, who had one measly church in Wichita. I, by contrast, had a whole world of churches, and I felt as welcome at each as I did at my home parish.

I also noticed that Protestants traveling with us tended not to go to church on Sundays. I could understand why, with childish magnanimity, because their church was back in Wichita. Our church, however, was wherever we happened to be. The Catholic church in the place we were visiting, which I might never see again, was still my church, because Jesus welcomed me.

It was therefore disconcerting (that word again) when, in the 1980s, people started saying things like: "Welcome to our parish family." Family implies inclusion and exclusion—try walking uninvited into another family's house at Thanksgiving and see what happens. The statement suggested the parish I was visiting was somehow different than my home parish. But I had never felt that way. We are all Catholic, right? Isn't my welcome here, and that of everyone besides, from Christ?

I desperately wished, for reasons of both piety and common sense, to receive from the hand of a priest at an altar rail.

So, the first major crises occurred in the late-1990s, when this "welcome to our parish family" ecclesiology received ritual form. Well-meaning people installed official "greeters," almost always strangers to me, at all church doors. We were told, of course, that everyone would now feel welcome.

I sometimes think the people responsible for the New Mass do not understand communication. Symbols take their meaning from the society which uses them. In our society, an official like this is placed at the entrance of a place to which the visitor does not belong.

We are not talking here of an usher opening a door, a friend saying hi in the narthex, or a parishioner asking if we need help. The church greeters were performing the same function as greeters in stores, restaurants, and airliners perform. The message was therefore the same—I was a mere invitee, present on the sufferance of management.

I cannot describe my astonishment. As a friend put it, the greeters were arrogating to themselves the role of Christ. It was no longer Christ who greeted me, but the parish organization, and I would only get to Him through them.

As I said, my reaction may seem silly or ridiculous, but it was also nearly fatal. The demoralization was enough to make continued attendance seem impossible. I only survived by playing along, greeting the greeters with suitable gusto, until I could wade past, genuflect before the Tabernacle, and remember why I was there.

For the second major crisis, we have the internet to thank. I came across the blog maintained by Fr. John Zuhlsdorf, which at that time was devoted to an examination of the translations used in the New Mass. I also construed texts in my work as a lawyer, and I appreciated the rigor of Father's approach.

There was something more, however. Fr. Z was the first person I had encountered willing to make a clear and unreserved defense of the Catholic liturgical tradition. I eventually realized that hints had been dropped earlier in my life, for example in seminary liturgy class, but only with Fr. Z did the "Old Mass bad, New Mass good" narrative of my youth meet substantial headwind.

I need to emphasize, however, that at no time did I consider attending the Traditional Mass. My conditioning ensured that any traditional impulses would remain focused on the New Mass. At that point in Church history, such a focus was not as incredible as it might now sound.

It is a horrible thing to think that you can save your soul only by attending a ritual that is destroying your mind.

We were in the "reform of the reform" era. Pope Benedict XVI was on the throne, and I read every book of his I could find. I attended a lecture by a Roman university professor on the pope's "hermeneutic of continuity." It was possible to think the New Mass could move towards tradition as well as away.

To take a specific example, consider communion in the hand. After much study and thought, I decided to receive communion on the tongue. This was a great improvement, but lay people were still touching the Eucharist. In addition, because communion was distributed standing and I was not any shorter, there was still a problem with the angle of attack. I desperately wished, for reasons of both piety and common sense, to receive from the hand of a priest at an altar rail.

Today, such aspirations would be understood with reference to the Traditional Mass. But 10 or 15 years ago, that was not necessarily the case. Moreover, I had personally received in such a fashion at my First Communion, and for a few years thereafter. Those were all New Masses, at least of the initial sort.

A similar analysis applies to the orientation of the priest during Mass. When I fully understood the priest had not prayed with his back to the people, but in the same direction as the people, it seemed a perfect cure for my stress. I longed for a priest who would turn around and pray to God. I wanted a Mass where he didn't even know I existed, where I was a bug or speck of dust behind him, where the Mass was about God and not about me.

None of this, however, suggested to me the Traditional Mass. As I understood it, the 1970 rubrics permitted, or even presumed, celebration ad orientem. I knew the Church had given us the New Mass, and I wanted to be a good Catholic. But I also wanted the priest to face God.

What was happening, of course, was that I was developing Catholic liturgical ideas to go with my Catholic liturgical instincts. When these coalesced, my view of the liturgy firmed up. The liturgy, however, refused to change. Communion remained the same, and the orientation of the priest remained the same. This was the New Mass, and the ratchet only worked in one direction.

The upshot was a significant increase in my pain. I was attending a liturgy each week that did not fully match my beliefs. Once again, I know of no other way to put it.

My experience after a few years can only be described as torture. I was locked into the New Mass, and it was killing me. I am no superman, so this could not last for long.

I broke in September 2011, roughly 40 years after my First Communion. Driving by myself to Mass on Sunday, I began screaming in an uncontrollable rage. I knew what was coming: the talking, the dress, the emoting from the altar, the disrespect for the Blessed Sacrament.

I still could not believe I might attend the Traditional Mass. I felt like a loathsome rebel.

My behavior seriously disturbed me. Given my mental health history, I did not think I should risk another episode.

I wonder how many bishops and priests consider that some Catholics may avoid Mass not for lack of faith, but for self-preservation. I have good reason to believe I was to that point by September 2011. It is a horrible thing to think that you can save your soul only by attending a ritual that is destroying your mind.

I was one the lucky few, however. I knew of an F.S.S.P apostolate in a neighboring city. So I actually had three options: personal destruction, apostacy, or the Traditional Mass. It was this choice, and not the Second Vatican Council, a political philosophy, or anything else, that led me to consider the Traditional Mass.

I spent a very difficult week. On Sunday, I suited up and drove to an intersection in town. I sat there for what was probably an illegal length of time.

Turning one direction would take me, in a mile and a half, to the New Mass I had long attended, where I sang in the choir and had many friends. Turning the opposite direction would take me out of town, through 25 miles of countryside, to a Traditional Mass I did not know, with people I had never met.

I still could not believe I might attend the Traditional Mass. I felt like a loathsome rebel. But the memory of my outburst was clear, and I didn't think I could scream in rage every Sunday on the way to Mass. So, reminding myself Pope Benedict approved the Mass I was about to attend, and that the local archbishop did too, I turned and drove out of town.

I will not describe my experience at that Traditional Mass, nor at the many since. I probably would only summarize what better and more scholarly writers have already said. I could point, for example, to an essay by Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, published at New Liturgical Movement on July 26, 2021, which reaches the difficult-to-specify distinction between a liturgy concocted by a group of experts and one which has grown over centuries from the community itself.

I instead will describe that first Sunday afternoon, now almost 10 years ago. Arriving back in town, I got a lawn chair and placed it squarely in the middle of my driveway. I have no idea why. I had never done so before, and I have not since.

I sat there in the sun. It was a beautiful, warm, early-fall day. I could hear university sounds from the distance, perhaps a band practicing. Across the street, children played.

In retrospect, I think my mind was almost stunned. I could sense an idea moving about its perimeter, but I did not want to focus. I judged the idea too small to bother with, or was it too big?

When I was ready, the idea let itself in: I was not depressed! For the first time in over two decades, my mind was not dropping into blackness. I was not, even temporarily, in an abyss of painful despair.

I was just a guy in the sun, feeling contented, serene and, finally, at home.