Claudel was an 18-year-old student who had abandoned religious practice and wandered through the streets of Paris, restless and dissatisfied with himself when, on the night of Christmas Eve, he entered into the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, while the choir was singing what he later learned was the Magnificat. He recounts:

I was standing in the middle of the crowd, near the second pillar from the choir entrance on the right, on the sacristy side. In that moment I understood the event that dominates my entire life. In an instant my heart was touched and I believed. I believed with a strength of adhesion so great, with such an uplifting of my entire being, with a conviction so powerful, in a certainty that did not leave place for any sort of doubt, so that, afterwards, no reasoning, no circumstance of my agitated life was able to shake my faith nor touch it. Suddenly I had the piercing feeling of innocence, of the eternal childhood of God: an ineffable revelation!

Seeking to reconstruct the moments which followed this extraordinary instant – as I have often done – I have rediscovered the following elements that, however, form one single flash of lightning, one single weapon used by Divine Providence to finally succeed in opening the heart of his poor desperate son: “How happy are the persons who believe!” But was it true? It was really true! God exists, He is here. He is someone, a personal being like me. He loves me, He calls me. Tears and sobs had sprung up, while my emotion had grown even greater due to the sound of the tender melody of “Adeste, fideles” [...].

Paul Claudel understood that evening, in a flash, with invincible evidence, that the life of each one of us opens wide before an inexorable alternative: either the infinite love of God or eternal damnation. He recalls further:

It is true – I confess it with the Roman centurion – that Jesus was the Son of God. It was to me, Paul, who he turned and promised his love. But, at the same time, if I did not follow him, he left me damnation as the only other alternative.

Ah, I did not need to have explained what hell was: I had already done my time there. Those few hours were enough to make me understand that Hell is anywhere there is not Christ. What did I care about the rest of the world, in front of this new and prodigious Being that had been revealed to me?

The life of Paul Claudel became the attempt to remain faithful to the grace of the Christmas of 1886, “the day of Christmas in which every joy was born,” as he wrote in his most famous work, L’Annonce faite à Marie (1912).

The Social Aspect of Holy Christmas

But the feast of Holy Christmas does not only have an individual and family signifiance: it also has, and has had in history, a social significance. The great abbot of Solesmes, Dom Prosper Guéranger (1805-1875), in his L’Année Liturgique, recalls for us three moments of Holy Christmas linked to the history of Europe, to its deepest Christian roots.

The first of these moments is the baptism of Clovis, which took place, according to tradition, on December 25, 496.

Clovis was the king of the Franks, a people that was still pagan, while Christianity was spreading in a Europe prey to chaos and anarchy after the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, which had taken place twenty years earlier. He had married Clothilde, a Catholic princess of the people of the Burgunds. It was she, with the help of Remigius, the holy bishop of Rheims, who brought Clovis to the Catholic religion, conquering his heart.

Clovis had himself baptized on the night of Christmas in the year 496.

The historian of the Franks, Gregory of Tours, writes that Clovis “approached the lavacrum [bath] like a new Constantine, to be freed from the ancient leprosy, to dissolve in fresh water the lurid stains that had been created over a long period of time. And when Clovis had entered the Baptistry, the saint of God said to him with solemn words: “Meekly bow your head, O Sicambrus. Worship what you have burned, burn what you have worshipped.”

The baptism of Clovis was the baptism of a people who, with him, entered into history: the Franks. And according to Dom Guéranger, the supreme Lord of events willed that the King of the Franks would be born on the day of His Nativity to impress more deeply the importance of such a holy day in the memory of the Christian peoples of Europe.

Clovis, the proud barbarian, humble as a lamb, was immersed by Saint Remigius in the baptismal font of salvation, from which he emerged purified in order to inaugurate the first Catholic monarchy among the new monarchies, the Kingdom of France, the most beautiful of all kingdoms – it is said – after the kingdom of heaven.

The Conversion of England

One hundred years passed from the conversion of Clovis. There arose to the pontifical throne a great pope, Saint Gregory the Great. In 596, according to what is remembered, Pope Gregory was moved at seeing, in the slave market of Rome, a group of young people who were blonde and beautiful as angels. He asked who they were, and the answer was: Angli.

“Non Angli, sed Angeli,” replied the Pope, who from this moment decided to entrust the evangelization of England to the Benedictine monks. A group of forty monks, guided by Augustine, later known as “Augustine of Canterbury,” left for the island of the Angles in order to spread the Gospel.

Augustine, after converting King Ethelbert to the true God, went to the city of York, which was already Roman, and there he made the Word of Life resound, and an entire people joined their king in asking for Baptism. And so it happened: the baptism of the king was the baptism of an entire people, linked to their sovereign by chains of indissoluble fidelity.

The day of Christmas was chosen for the regeneration of these new disciples of Christ; and the river that flowed under the city walls was chosen to serve as the baptismal font for an army of ten thousand catechumens, not counting women and children. The rigor of the winter season did not stop the new and fervent disciples of the Child of Bethlehem, and they went down into the icy waters to purify their souls.

Dom Guéranger writes: “From the icy waters an army of neophytes emerged, full of joy and resplendent in innocence; and on the very day of his birth, Christ counted one more nation under his empire.”

Saint Augustine of Canterbury was the evangelizer of Britain, and then in turn monks set out from England and Ireland, following another great missionary, Saint Boniface, to evangelize Germany.

The Coronation of Charlemagne

Another illustrious event was yet to embellish the anniversary of the Nativity.

On the Solemnity of Christmas in the year 800, with the coronation of Charlemagne at Rome, the Holy Roman Empire was born, to which was reserved the mission to propagate the kingdom of Christ in the barbarous regions of the North and to maintain European unity under the direction of the Roman Pontiff.

The King of the Franks in the year eight hundred after Christ had already subjugated the Aquitaines and the Lombards; he had crossed the Pyrenees in order to tame the threatening power of the Arabs in Spain; he had put down the insurrection of the Saxons and Bavarians; and he was in full battle against the Avars.

He was not only a warrior: under his influence, the arts and sciences flourished throughout all of Europe. He was greatly loved by his subjects, venerated by his warriors, and in all the lands he conquered he extended the beneficent influence of the Catholic religion.

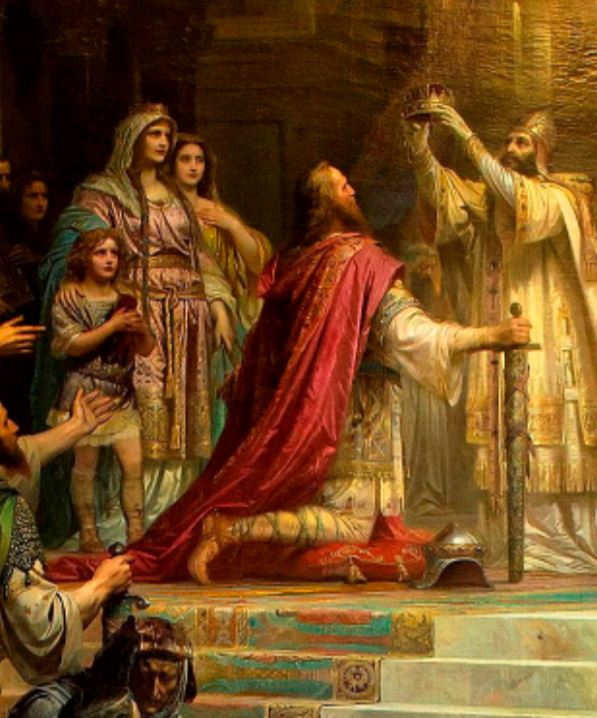

And now Charlemagne, the heir of Clovis, entered into Saint Peter’s Basilica, on a Christmas night that was cold thanks to the rigors of winter, but warm thanks to the atmosphere of enthusiasm that reigned in the Basilica. The King of the Franks knelt down, lowered his head, adoring God made man and imploring mercy for his sins. He beat his breast and had recourse to the intercession of the Virgin Mary, without realizing that someone was approaching him in silent respect. It was not a simple priest or bishop – it was a pope, a holy pope. The chronicles recount that “at the moment in which the king rose up from prayer, during the Mass, before the altar of the confession of Saint Peter the Apostle, Pope Leo III came up to him and placed a crown on his forehead.”

A new crown, not that of King but of Emperor.

The pope, Saint Leo III, placed the imperial crown on the head of Charlemagne; and the astonished world saw once again a Caesar, an Augustus, no longer a successor of the Caesars and Augusti of pagan Rome, but invested with those glorious titles of Vicar of He whom Scripture defines as the King of Kings, the Lord of Lords. The Roman people acclaimed him with these words: “to Charles Augustus, crowned by God as great and pacific emperor of the Romans, life and victory,” while the Franks, beating their spears on their swords, raised up the cry, “Christmas, Christmas [ Natale, Natale],” a cry that, ever since the time of Clovis, recalled the entrance of their people into history.

Two days before the coronation, a monk of Saint Saba and a monk of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem had offered to the king of the Franks, as a gift from the Patriarch, “the keys of the Holy Sepulchre and of Calvary and the keys of the city and Mount Zion with a banner.” It was a symbolic homage, a new halo of sanctity placed around the forehead of the king who had extended his protection across the seas, who would protect the Christians of Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Tunisia.

On that Christmas, in the Cathedral of the Vicar of Christ, there was born the Catholic Empire of the West, the pillar of medieval Christian civilization – just as 800 years earlier, on the very same day, the Baby Jesus was born in a manger.

In founding the Apostolic Roman Catholic Church, Jesus Christ had placed in her, in seminal form, all of the potentialities needed to generate a great civilization.

With the expansion of the Church, with the conversion of the peoples over eight centuries, the seed developed, became a concrete possibility, and finally bloomed in the year 800 in the empire of Charlemagne, blessed and ratified by the hands of a holy successor of Peter. It was the beginning of an era in which, as Leo XIII teaches in his encyclical Immortale Dei, “the priesthood and the empire were linked together by a happy concord and by the friendly exchange of services” and “organized in such a way that the civil society yielded fruits that were superior to every expectation.”

Another pope, John Paul II, on the occasion of the 1200th anniversary of the coronation of Charlemagne, recalled: “The great historic figure of the emperor Charlemagne recalls the Christian roots of Europe, carrying all those who study it back to an era that, despite its ever present human limits, was characterized by an imposing cultural flourishing in almost every field of experience. In search of its identity, Europe cannot leave aside an energetic effort to recover the cultural patrimony left by Charlemagne and preserved for more than a millennium.”

Charlemagne was great not only because of his victorious wars from one end of Europe to the other, but above all through his work of juridical, cultural, and artistic restoration, inspired by the principles of the Gospel. At a time of decadence and disorder, he can be considered as the founder of Christian Europe. With the first Christian Emperor, the West for the first time acquired self-awareness and presented itself on the stage of history conscious of its own Christian and Roman unity.

The coronation of Charlemagne was in addition a public and symbolic act of universal importance, destined to express, for more than a millennium, the conception of sovereign Christianity. The font of authority is the representative of God on earth, because – on earth – no authority exists that does not originate from God. In this sense the coronation of Charlemagne may be considered as the Nativity of Christendom.

What was at one time Christendom is today agonizing under the attacks of enemies both external and internal, and we await with trepidation a new day of Nativity, a day of birth and resurrection for our souls and for all of society: the blessed day, announced at Fatima, of the triumph of the Church and the restoration of Christian civilization.