The Albertine Statute was adopted in 1861 as the constitutional charter of the new King of Italy and remained in force until the fall of the Monarchy in 1946. The republican constitution of 1948 abolished the principle of the confessional State, but in its Article 7 it accepted the Lateran Accords, which in Article 1 of the Treaty reaffirmed the principle by which “the Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Religion is the only religion of the State.” This principle is the basis for the recognition on the part of the Italian State of the “sacred character” of the City of Rome and the resulting commitment by the authorities to prevent the Eternal City from being profaned by activities conflicting with this sacred character: “In consideration of the sacred character of the Eternal City, the episcopal see of the Supreme Pontiff, the center of the Catholic world and a place of pilgrimage, the Italian Government will take care to prevent in Rome anything which could be in contrast to this sacred character.”

In 1938, on the occasion of the Hitler’s visit to Rome, Pius XI referred to this article, deploring the fact that the sign of a cross which was not the Cross of Christ was raised over the sacred City of Rome. But even in 1965, on the occasion of the representation of Rome in the theatral pièce of Rolf Hochhuth, Il Vicario, which was seriously prejudicial to the memory of Pius XII, after the Holy See protested, the police made the theater close and the Prefect of Rome outlawed the show because it was contrary to the norms contained in the Concordat.

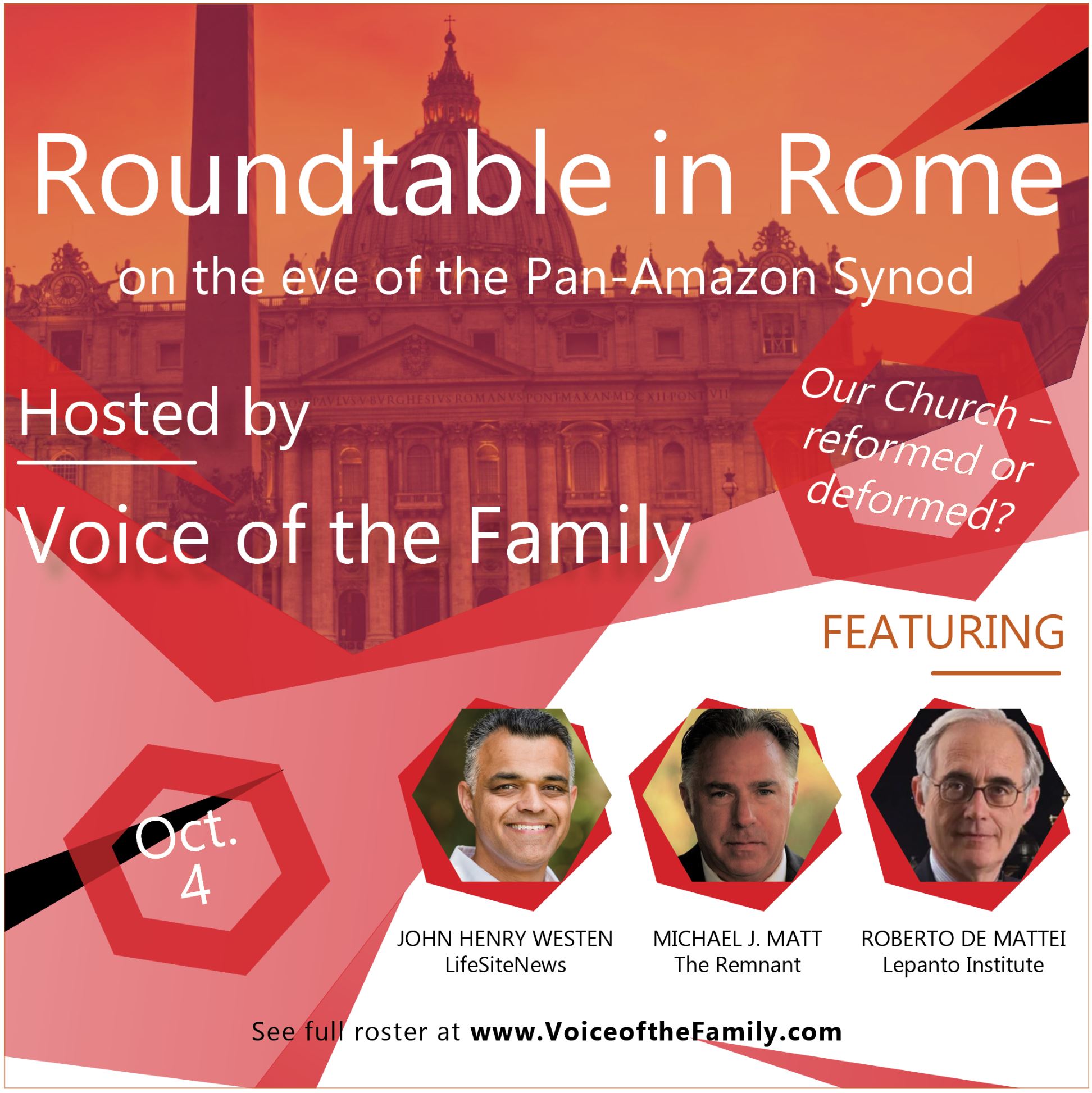

This article appeared last month in the print/e-edition of The Remnant.

Click the Pic to Preview the September 15, 2019 Edition:

To see what else you've been missing, subscribe today!

Twenty years later, on February 18, 1984, the president of the Consiglio, Bettino Craxi, and the Cardinal Secretary of State, Agostino Casaroli, solemnly signed the revision of the Lateran Accords of 1929. This revision was radical enough to justify talk of a “New Concordat.”

The fundamental novelty of the New Concordat, as Craxi himself explained, consisted in the realization of the “modern separation” between Church and State, affirming the principle of the “neutrality” of the State in matters of religion (Intervention in the Italian Senate of 25 January 1984). Cardinal Casaroli specified that the “fulcrum” of the New Concordat was contained in its first article, in relation to which, in an additional Protocol, it was explicitly stated: “The original principle referred to by the Lateran Accords of the Catholic religion as the only religion of the State, is considered to be no longer in force.”

Thus we are not speaking about a simple revision, but of “a new model of concordat,” as declared by Msgr. Vincenzo Fagiolo, the Vice-President of the Italian Episcopal Conference, “quite different from the models which have characterized the rapport between Church and State for the last two centuries in particular (Per un vero servizio al Paese, in Avvenire, 25.1.1984.). Disowning the principle of the Lateran Accords – according to which “the Catholic, Apostolic, Roman religion” was considered to be “the only religion of the State,” while other religions were simply tolerated – the New Concordat establishes the equality of all religions before the State.

The Magisterium of the Church, above all through the mouth of the Supreme Pontiffs, has always condemned the principle of religious freedom or neutrality, affirming the duty of the State to publicly recognize and efficiently support the true Religion. The spiritual and temporal order are actually two distinct, but not separate, realities. The Church and State watch over each of these realms, respectively. The collaboration between these two sovereign powers has its foundation in the principle according to which society and States have the duty to recognize the true religion and profess it publicly.

The Church teaches that a State which fails to recognise Catholicism publicly as the true religion must be considered agnostic as far as religion is concerned, and therefore ultimately atheist. This is the position taken up in the 19th Century by Pope Gregory XVI in Mirari Vos (1832), by Pope Pius IX in Quanta Cura and the Syllabus of Errors (1864), and by Pope Leo XIII in the encyclicals Immortale Dei (1885) and Libertas (1888). In Immortale Dei, Leo XIII claims that “to hold, therefore, that there is no difference in matters of religion between forms that are unlike each other, and even contrary to each other, most clearly leads in the end to the rejection of all religion in both theory and practice. And this is the same thing as atheism, however it may differ from it in name.” And in the encyclical Libertas of 20 June 1888, Pope Pecci went on to affirm that “Justice therefore forbids, and reason itself forbids, the State to be godless; or to adopt a line of action which would end in godlessness; namely to treat the various religions (as they call them) alike, and to bestow upon them promiscuously equal rights and privileges.”

The popes have always taught that the State must, at least in theory, recognise the true religion. The State may practice religious tolerance should critical circumstances demand it, but the Catholic paradigm cannot be that of a neutral stance on religion by the state. One must, however, not confuse the actual situation in which Catholics, for example in the United States, may find themselves – countries where the Church cannot do more than claim her right to freedom of action within a pluralist milieu – from that of other states of ancient Catholic tradition, such as Italy, where the Church, according to the Pontiffs, not only has the right to claim such freedom but also the entitlement to see the State publicly recognise it as the true religion.

The process of secularization of society which, beginning with the French Revolution, has covered Western Christianity, denies the principle of the confessional State. But what appears surprising is that, above all after Vatican II, the opposing principle of the religious neutrality of the State has been promoted above all by ecclesiastical authority. In 1984, on the eve of the signing of the New Concordat, the Lepanto Cultural Center issued a manifesto titled “Can A Catholic Prefer The Atheist State?” in which it declared:

It is not surprising that the revolutionary and anti-Christian forces, which profess atheism and radical egalitarianism, express their substantial satisfaction with a concordat project in which they see the principle of equality of religions affirmed, and thus an implicit atheism of the State, destined to have enormous consequences in civil society. What is instead amazing is that the same intimate satisfaction for this Concordat is being expressed publicly by the leaders of the Catholic world, both lay and ecclesiastic, to the point that they consider it much better than the former concordat and therefore clearly preferable.

Can a Catholic prefer a “neutral” State in matters of religion, which is thus implicitly atheist, to a State that is officially Catholic? Does not such a preference contradict Catholic doctrine and common sense itself?

Furthermore, this same common sense demands that a Catholic have the right to live in a society in which customs, laws, and institutions undergo the deepest influence from the true religion. The same logic demands that a Catholic claim the irrevocable right to form a Catholic family, a Catholic civilization, and a State that is Catholic in principle and in fact. The actual situation can make it impossible to live it out, but a Catholic ought to desire with all of his heart that Christ reign in the laws and in society.

In contrast, it is absolutely illogical that a Catholic would prefer a liberal and “neutral” State to a State that is declaredly Catholic.

If in the Lateran Accords the principle of the Catholicity of the State found its first confirmation in the affirmation of the sacred character of Rome, in the New Concordat this sacred character was abandoned. The fourth section of Article 2 of the text in force affirms instead that “the Italian Republic recognizes the particular significance that Rome, the episcopal See of the Supreme Pontiff, has for Catholicity.” This is a formulation that is absolutely generic and lacking any specific commitment on the part of the state. There is no reference to the sacrality of Rome nor is there any duty to protect its value.

Every affirmation of principle carries with it consequences of fact. If the Italian republic professes religious neutralism, and if the Church makes this position its own, the character most in keeping with this principle is not the Catholicity of Rome, but rather the “ecumenicity” of the City, recognized as a value by the Holy See itself.

In the same year as the New Concordat, the cornerstone was laid for the Mosque of Rome. On June 21, 1995, the Grand Mosque was solemnly inaugurated. It is the biggest Islamic temple in Europe, built right in the city that is symbolic of Catholicism, despite the tiny number of Muslims present in Italy at that time. The Lepanto Cultural Center again raised its voice in protest:

...not against a building, but against what the building represents: the project of the Islamization of the Europe beginning from Rome, the heart of Christianity. And the Islamization of Europe is not yet an accomplished fact. It could become that, certainly, as the construction of the mosque has become an accomplished fact, if in the name of a misunderstood ecumenism the threat of Islam continues to be ignored: a threat which the construction of the mosque makes more palpable and evident.

In Rome in July 2000, at the height of the celebrations of the Great Jubilee Year proclaimed by John Paul II, the first “world day of homosexual pride” took place, a blasphemous affront brought into the very heart of Christianity. Rome, no longer sacred, became the theater for a frontal provocation against the Church, and the ecclesiastical authorities were no longer able to make any appeal to the Lateran Accords in order to prevent this scandal.

The same logic which thirty-five years ago led to the abolition of the Lateran Accords and to the affirmation of the principle of the religious neutrality of the State, today is leading to the transformation of the City of Rome into the capital of the reception of migrants, as Pope Francis said in his meeting on March 26, 2019, with Mayor Virginia Raggi, hoping “that Rome should live up to the greatness of its duties and its history, so that it knows even in today’s changing circumstances how to be a beacon of civilization and a master of welcoming, that it may not lose the wisdom which is shown in the capacity to integrate each person and make them feel the fullest title of a common destiny.” In the new lay and ecumenical perspective, the Concordat with the Italian State, whether new or old, no longer has any reason to exist. The symbol of the vocation of Rome is no longer Saint Peter but the pagan Pantheon, such as resulted in the exaltation of pagan polytheism which is present in the Instrumentum Laboris for the Synod on the Amazon.

Will the Church, beginning this coming October, lose its Roman face in order to assume an “Amazonic face”? Somebody wants this to happen, but he is not in the Amazon, he is in Rome where Saint Peter was martyred, the Apostle on whom Christ conferred the universal Primacy. And it is on this martyrdom, not on the Lateran Accords, that the greatness and sacrality of the Eternal City is based. The Catholic Church is intrinsically Roman and Rome is intrinsically Christian. Rome is in fact, by the will of Divine Providence, the seat of the Chair of Peter, the heart of the Church, the mother of civilization, the center of Catholic unity, the moral and spiritual capital of the world. She testifies to the nations “the indefectible permanence, across all times, of the Church founded by Christ, the depository of revealed Truth and of the promise of salvation (Pius XII, Discourse of July 20, 1955). Today this sacrality lives above all in our hearts, in which resound the words which the same Pius XII addressed to the young students of Rome on January 31, 1949:

If ever one day (let’s just say so as a mere hypothesis) the material Rome should collapse, if ever this same Vatican Basilica, symbol of the one, invincible and victorious Catholic Church, should bury under its ruins the historic treasures, the sacred tombs that it contains, even then the Church would be neither broken down nor cracked; the promise of Christ to Peter would remain ever true. Eternal Rome, in a supernatural Christian sense, is superior to historical Rome. Her nature and her truth are independent of this.

Translated by Giuseppe Pellegrino