“Miguel Pro!”

Crowds stirred. Heads turned. Flashbulbs popped atop leather-bellow cameras.

Forward, stepped the Jesuit. Religious garb had been outlawed in Mexico the previous year, 1926, so the 36-year-old Roman Catholic priest wore street clothing that he’d slept in while locked up the last six days: rumpled black jacket and pants, white shirt and a tie tucked into a button-down sweater vest with a horizontal zigzag pattern.

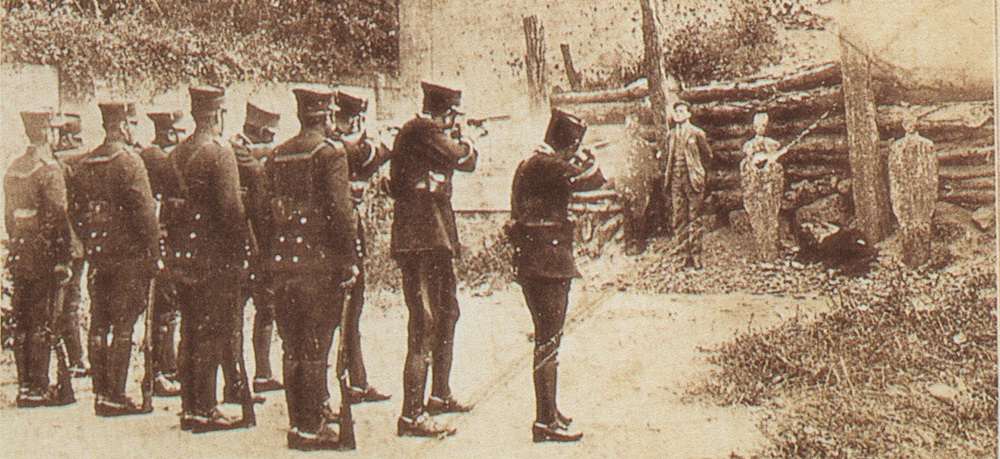

Escorted by two men wearing overcoats and fedoras, the three proceeded into a secured, wall-enclosed courtyard filled with reporters, photographers, uniformed soldiers, mounted police and even representatives of the diplomatic corps. In the center of all, stood four teams of five-man firing squads. Nearby, two Green Cross ambulances waited for the bodies.

Among the observers stood Roberto Cruz Diaz (1888-1990), chief police inspector and veteran general of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). He dressed in a brand-new uniform for the occasion: jodhpurs and jackboots, high-collar jacket wrapped in a Sam Browne belt including shoulder strap, and a visored cap with an enamel tri-color cockade displaying the colors of the Mexican flag: green for hope, white for purity, red for bloodshed, lots of bloodshed. Relaxed, he stood casually, leaning his weight onto his left leg, as he sucked on a smoldering cigar.

Cruz admired himself, thought of himself as a cultured man, certainly not an old-fashioned, religious believer in cockamamie superstition. An apostate who turned his back on the Roman Catholic Church, he scornfully looked at the priest, who stared straight ahead as he walked by, calmly, silently. The General – tapped to oversee the executions – noticed that the blood had drained from the face of the condemned man. His dark skin appeared pale. His lips, like paper. But the face – Cruz grudgingly admitted to himself – appeared intelligent and cultured.

At the shooting range, the priest, the Alter Christus, stopped before the human silhouettes used for target practice. The lifeless figures – pockmarked with bullet hits – stood askew in front of stacked logs protecting a small section of the concrete wall that surrounded Mexico City’s Federal District General Police Inspectorate.

“Any last requests?” asked Major Torres, commander of the firing squads.

“Yes, I want to pray a little.”

Upon the earth, he kneeled, slowly crossed himself, blessing himself, and clasped his hands in prayer, reminiscent of Albrecht Durer’s pen-and-ink “Study of the Hands of an Apostle.”

Reverently, he kissed the small crucifix that he had removed from around his neck. On his knees, in front of the firing squad, he calmly pulled from his pocket a rosary and then stood with such a determined enthusiasm that it briefly softened some of the stone-hearted soldiers – his executioners – assembled in front of him.

The priest refused a blindfold, kissed the crucifix in his right hand and gripped the rosary dangling from his left, as he faced death.

“Attention!” Major Torres called to the death squad waiting orders.

“God is my witness that I am innocent of the crime you impute to me!” declared the priest.

“Step in!”

Five snappy-uniformed soldiers stepped forward and formed a line.

“God have mercy on you all,” prayed the priest for his killers, and with his crucifix he made a large sign of the cross over the gunmen.

“Ready!” yelled the commander, raising his right arm, brandishing a sword, pointed heavenward.

“With all my heart, I forgive my enemies.”

“Aim!”

In an act of philopassionism, the priest thrust his arms out to the side, in imitation of Christ, raised his eyes to the skies and slowly, distinctly shouted, “Viva Cristo Rey!”

“Fire!” the commander yelled, with a swift downstroke of his sword.

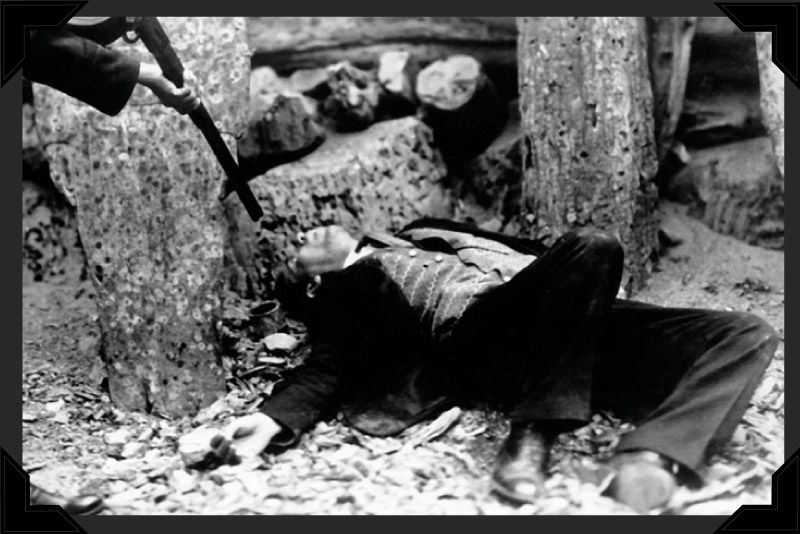

To the ground, the priest collapsed.

Police Medical Doctor Horacio Cazale walked over and found him still alive, but quickly remedied when a gunman, the squad’s officer, a sergeant, pointed his rifle a few inches from the right side of the priest’s head and administered the exploding coup de grace.

It was 10:30 in the morning, November 23, 1927. A Wednesday.

“Luis Segura!”

Forward stepped a 24-year-old man, dressed in a light-colored, three-piece business suit, with a tie tucked into his vest and a handkerchief sticking out of his jacket’s chest pocket. Escorted from his basement jail cell to the courtyard, he advanced toward the wall. As he neared the body of the priest, he stopped, respectfully bowed, and then proceeded a few more steps.

“Do you want to be blindfolded?” Torres asked him.

“No. I am ready, gentlemen,” he answered, sliding his hands into his trouser pockets, then quickly removed them, swinging them behind his back, thrusting out his chest, prepared to receive the bullets.

Silence, as Segura looked ahead, serenely.

Cruz looked at him with admiration, for his bravery, for his steel-bound acceptance of it all.

“Attention!”

“Step in!”

The second squad of five riflemen stepped forward.

“Ready!”

Major Torres raised his sword.

Executioners raised their long guns to their shoulders.

“Aim!”

“Viva Cristo Rey!” Segura yelled.

“Fire!”

Sword dropped. Rifles fired.

From the impact of the bullets, Segura’s arms swung forward, and he fell to the ground, face forward.

“Humberto Pro!”

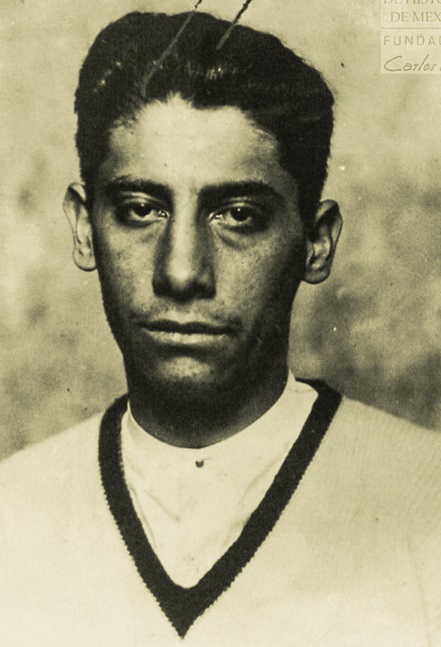

As he neared his elder brother sprawled on the ground, he lovingly touched the dead priest with his foot, a final loving gesture. He stood, positioned between the bodies. His straight black hair, slicked back. Under his jacket, a white cricket sweater that would soon soak up his blood.

He, too, refused a blindfold.

“Attention!”

“Step in!”

The third squad stepped forward.

“Ready!”

“Aim!”

“Viva Cristo Rey!” yelled the 24-year-old.

“Fire!”

He fell, on his back, near Segura.

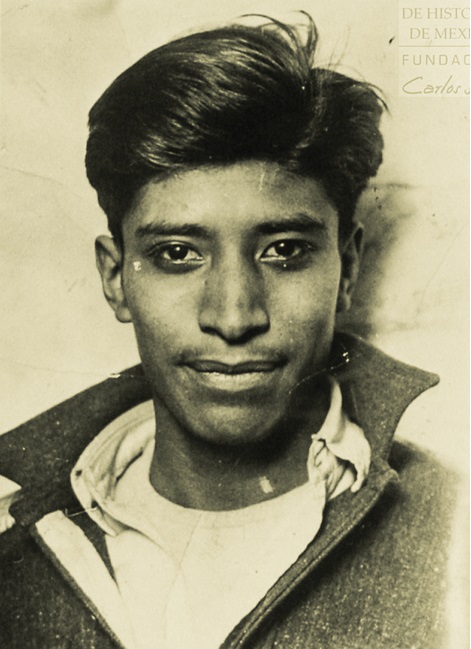

“Juan Tirado!”

Cruz stared at the shivering 20-year-old Tirado, an impoverished worker suffering from pneumonia. Wrapped in a blanket, he stood among the three crumpled, bloodied bodies.

Why would he want a blanket, if he is soon going to be cold, cold forever? thought Cruz.

In the preceding days, Tirado had suffered horrendous water torture between interrogations intended to coerce him to talk, to inform against others. With his mouth tightly gagged, his tormentors slipped a water hose through a slit between his lips and turned on the tap. Water gushed into his mouth, choking him as it forcefully rushed down his throat, flooding his stomach, causing sharp pains that caused his body to convulse.

But nothing. He revealed nothing, saying only that he knew nothing about the assassination attempt, that he had simply been waiting nearby for a train and was merely curious about the commotion on the street when he was captured.

Standing before the execution wall, he was asked a final question.

“Any last request?” asked Torres.

Weak from torture, he barely gasped, “I want to see my mother.”

“Impossible! Put your back to the wall!”

“Attention!” announced Torres, with sword in hand.

“Step in!”

“I want to see my mother,” Tirado repeated.

“Ready!”

“Aim!”

“I want to see my mother!”

“Fire!”

The line of gunmen fired, hit their flesh-and-blood target, spinning him around, before he fell sideways to the ground, face down.

Newspaper photographers from the national broadsheets Excelsior and El Universal rushed over to the bodies and snapped close-up shots of the four dead believers. El Universal Grafico even ran a special edition, which the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty – a Catholic group the men belonged to – quickly snapped up.

And the published photographs did what all the League-produced pamphlets and leaflets detailing the religious persecution could not do: immediately impact the faithful. Photos revealed the truth that could not be denied by Mexican President Plutarco Elias Calles (birth name: Francisco Plutarco Elias Campuzano, 1877-1945), or by his Socialist government or by the Callistas, his supporters.

An old Bolshevik tactic, Calles intended to use the executions as a warning to terrorize Catholics into submission with the stark newspaper coverage. But it failed. Thoroughly. Not only did the graphic images reinforce their faith, but it also united them even more so against the violent, intolerant, anti-clerical, anti-Christian government.

***

Placed upon stretchers, the four bodies were removed from the execution courtyard and transferred to the Military Hospital, where autopsies were hastily performed. Both Pro brothers had five bullet holes in their chests.

Placed in caskets, their sister Ana Maria Pro Juarez (1892-1936) was finally able to see them. As she kneeled beside the wooden boxes, she heard the voice of their recently widowed father, Miguel Pro Romo: “Where are my sons? I want to see them!”

Video Ad: Our Lady of Victory School

Raising the lids, he kissed the forehead of his eldest son Miguel and pulled a handkerchief from his own pocket to wipe the blood from the dead man’s face; he then kissed the forehead of Humberto.

With his daughter sobbing in his arms, he tried to reassure her, “My daughter, there is nothing to cry about.”

From the hospital, the Pro brothers were carried to their father’s home, at 5 Calle Rio Panuco, where thousands of faithful, including workers and even soldiers, flocked to see the martyrs, beginning at 5 that evening until nearly midnight. For the wake, a priest garbed illegally in vestments led the prayers, as the two executed men – wrapped in their eternal shrouds – lay in state. Upon the chest of the priest: a pyx containing the Blessed Sacrament.

On his knees beside his sons, the patriarch of the family sobbed, “The Father was an apostle; Humberto was an angel all his life, and they died for God. They are already with him in Heaven!”

Outside, the following morning, at 6 a.m., more men, women and children surrounded the home and demanded to see the brothers, martyred, each with a second baptism, the baptism of blood. Inside, pall bearers prepared the dead in their caskets and hoisted them, to transport them to their graves.

“Let the martyrs through!” shouted Miguel Palomar y Vizcarra, when the doors finally swung open, at 3 p.m.

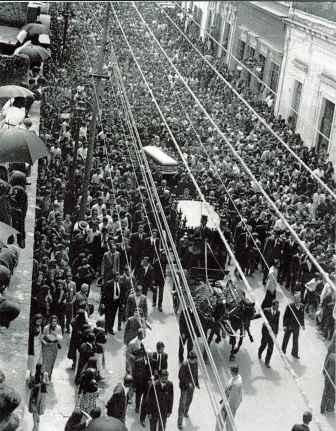

Silence gripped everyone, but as soon as the faithful saw the caskets borne aloft through the doorway, carried by priests, cries of “Viva Cristo Rey! Via Cristo Rey! Via Cristo Rey!” rose, followed by a spontaneous outburst of cheers and applause.

Thousands and thousands surrounded the martyrs. Mourners filled the streets from sidewalk to sidewalk along the Avenida Paseo de la Reforma, which ran across the heart of Mexico City, just as the martyrs ran across the hearts of Catholics. Many genuflected to honor the men and to acknowledge their sacrifice. From the streets below and the balconies above, faithful tossed bouquets and single blossoms upon the passing caskets.

“Long live the holy martyrs! Long live the Pope! Long live our bishops and priests!” they cheered.

During the 6.2-mile-long procession to the largest cemetery in Mexico, the Panteon de Dolores, mourners sang “Salve Cristo Rey,” heard by Calles, who opened the windows of Chapultepec Castle, the presidential residence, to view the cortege.

At the cemetery, thousands more waited, despite the threatening authorities who surrounded them.

Cries of “Long live the first Jesuit martyr of Christ the King!” rose from the crowd after the priest was entombed in the Jesuit’s crypt, Plot 35. With his brother interred nearby, their father was the first to throw shovels of earth into the grave.

“We have finished,” he said solemnly, and then began the first notes of, “Te Deum Laudamus,” a hymn of praise and thanksgiving to God, which the attending priests finished singing.

Amidst a great following, Tirado was laid to rest, and Segura was buried in the Panteon del Tepeyac in the Villa de Guadalupe, near the Basilica of Santa Maria of Guadalupe.

***

This story is a 3-part weekend series from The Remnant Newspaper.

The 2nd installment is HERE and Check back on Sunday, May 14, for the 3rd and final.

Latest from RTV — From TRANSgenderism to TRANShumanism: How Orwell Got It Wrong